History Essay Examples

Top History Essay Examples To Get Inspired By

Published on: May 4, 2023

Last updated on: Oct 28, 2024

Share this article

History essays are a crucial component of many academic programs, helping students to develop their critical thinking, research, and writing skills.

However, writing a great history essay is not always easy, especially when you are struggling to find the right approach. This is where history essay examples come in handy.

By reading and examining samples of successful history essays, you can gain inspiration, learn new ways to approach your topic. Moreover, you can develop a better understanding of what makes a great history essay.

In this blog, you will find a range of history essay examples that showcase the best practices in history essay writing.

Read on to find useful examples.

On This Page On This Page -->

Sample History Essays

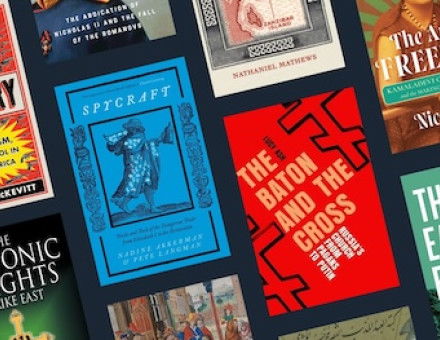

Explore our collection of excellent history paper examples about various history essay topics . Download the pdf examples for free and read to get inspiration for your own essay.

History Essay Samples for Middle School

The Impact of Ancient Civilizations on Modern Society

The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire

The Causes and Consequences of the American Revolution

History Writing Samples for High School Students

The Impact of the Industrial Revolution on Society

Grade 10 History Essay Example: World War 1 Causes and Effects

Grade 12 History Essay Example: The Impact of Technology on World War II

Ancient History Essay Examples

The Societal and Political Structures of the Maya Civilization

The Role of Phoenicians in the Development of Ancient Mediterranean World

The Contributions of the Indus Civilization

Medieval History Essay Examples

The Crusades Motivations and Consequences

The Beginning of Islamic Golden Age

The Black Death

Modern History Essay Examples

The Suez Crisis and the End of British Dominance

The Rise of China as an Economic Powerhouse

World History Essay Examples

The Role of the Silk Road in Shaping Global Trade and Culture

The Rise and Fall of the Ottoman Empire

The Legacy of Ancient Greek Philosophy and Thought

Paper Due? Why Suffer? That's our Job!

American History Essay Examples

The Civil Rights Movement and its Impact on American Society

The American Civil War and its Aftermath

The Role of Women in American Society Throughout History

African History Essay Examples

The Impact of Colonialism on African Societies

The Rise and Fall of the Mali Empire

European History Essay Examples

The Protestant Reformation and the Rise of Protestantism in Europe

The French Revolution and its Impact on European Politics and Society

The Cold War and the Division of Europe

Argumentative History Essay Examples

Was the US Civil War Primarily About Slavery or States

The Effects of British Colonization on Colonies

Art History Essay Examples

The Influence of Greek and Roman Art on Neoclassicism

The Depiction of Women in Art Throughout History

The Role of Art in the Propaganda of Fascist Regimes

How to Use History Essay Examples

History essay examples are a valuable tool for students looking for inspiration and guidance on how to approach their own essays.

By analyzing successful essays, you can learn effective writing techniques that can be expected in a high-quality history essay.

Here are some tips that will help you take full advantage of the samples above.

Tips for Effectively Using History Essay Examples

- Analyze the Structure:

Pay close attention to how the essay is organized, including the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion. Look for how the author transitions between paragraphs and the use of evidence to support their argument.

- Study the Thesis Statement:

The thesis statement is the backbone of any successful history essay. Analyze how the author crafted their thesis statement, and consider how you can apply this to your own writing.

- Take Note of the Evidence:

Effective history essays rely on using strong evidence to support their arguments. Take note of the sources and types of evidence used in the essay. Consider how you can apply similar evidence to support your own arguments.

- Pay Attention to the Formatting and Other Academic Formalities:

The sample essays also demonstrate how you can incorporate academic formalities and standards while keeping the essay engaging. See how these essays fulfill academic standards and try to follow them in your own writing.

- Practice Writing:

While analyzing history essay examples can be helpful, it is important to also practice writing your own essays. Use the examples as inspiration, but try to craft your own unique approach to your topic.

History essays are an essential aspect of learning and understanding the past. By using history essay examples, students can gain inspiration on how to develop their history essays effectively.

Furthermore, following the tips outlined in this blog, students can effectively analyze these essay samples and learn from them.

However, writing a history essay can still be challenging.

Looking for an online essay writing service that specializes in history essays? Look no further!

Our history essay writing service is your go-to source for well-researched and expertly crafted papers.

And for an extra edge in your academic journey, explore our AI essay writing tool . Make history with your grades by choosing our online essay writing service and harnessing the potential of our AI essay writing tool.

Get started today!

Cathy A. (Law, Marketing)

For more than five years now, Cathy has been one of our most hardworking authors on the platform. With a Masters degree in mass communication, she knows the ins and outs of professional writing. Clients often leave her glowing reviews for being an amazing writer who takes her work very seriously.

Need Help With Your Essay?

Also get FREE title page, Turnitin report, unlimited revisions, and more!

on 3 Purchases

Valid from 27th Nov to 1st Dec

Essay Services

- Argumentative Essay Service

- Descriptive Essay Service

- Persuasive Essay Service

- Narrative Essay Service

- Analytical Essay Service

- Expository Essay Service

- Comparison Essay Service

Writing Help

- Term Paper Writing Help

- Research Writing Help

- Thesis Help

- Dissertation Help

- Report Writing Help

- Speech Writing Help

- Assignment Help

Legal & Policies

- Privacy Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Terms of Use

- Refunds & Cancellations

- Our Writers

- Success Stories

- Our Guarantees

- Affiliate Program

- Referral Program

Disclaimer: All client orders are completed by our team of highly qualified human writers. The essays and papers provided by us are not to be used for submission but rather as learning models only.

- Written Essays

How to write source-based history essays

The biggest assessment task you will be required to complete is a written research essay which develops an argument and uses a range of sources.

All types of assessment tasks will need you to use essay-writing skills in some form, but their fundamental structure and purpose remains the same.

Therefore, learning how to write essays well is central to achieving high marks in History.

What is an 'essay'?

A History essay is a structured argument that provides historical evidence to substantiate its points.

To achieve the correct structure for your argument, it is crucial to understand the separate parts that make up a written essay.

If you understand how each part works and fits into the overall essay, you are well on the way to creating a great assessment piece.

Most essays will require you to write:

- 1 Introduction Paragraph

- 3 Body Paragraphs

- 1 Concluding Paragraph

Explanations for how to structure and write each of these paragraphs can be found below, along with examples of each:

Essay paragraph writing advice

How to write an Introductory Paragraph

This page explains the purpose of an introduction, how to structure one and provides examples for you to read.

How to write Body Paragraphs

This page explains the purpose of body paragraphs, how to structure them and provides examples for you to read.

How to write a Conclusion

This page explains the purpose of conclusions, how to structure them and provides examples for you to read.

More essay resources

What do you need help with, download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Make Lists, Not War

The meta-lists website, best essays of all time – ranked.

A reader suggested I create a meta-list of the best essays of all time, so I did. I found over 12 best essays lists and several essay anthologies and combined the essays into one meta-list. The meta-list below includes every essay that was on at least two of the original source lists. They are organized by rank, that is, with the essays on the most lists at the top. To see the same list organized chronologically, go HERE .

Note 1: Some of the essays are actually chapters from books. In such cases, I have identified the source book.

Note 2: Some of the essays are book-length, such as Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own . One book listed as an essay by two listers – Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet – is also regularly categorized as a work of fiction.

On 11 lists James Baldwin – Notes of a Native Son (1955)

On 6 lists George Orwell – Shooting an Elephant (1936) E.B. White – Once More to the Lake (1941) Joan Didion – Goodbye To All That (1968)

On 5 lists Joan Didion – On Keeping A Notebook (1968) Annie Dillard – Total Eclipse (1982) Jo Ann Beard – The Fourth State of Matter (1996) David Foster Wallace – A Supposedly Fun Thing I Will Never Do Again (1996)

On 4 lists William Hazlitt – On the Pleasure of Hating (1823) Ralph Waldo Emerson – Self-Reliance (1841) Virginia Woolf – A Room of One’s Own (1928) Virginia Woolf – The Death of a Moth (1942) George Orwell – Such, Such Were the Joys (1952) Joan Didion – In Bed (1968) Amy Tan – Mother Tongue (1991) David Foster Wallace – Consider The Lobster (2005)

On 3 lists Jonathan Swift – A Modest Proposal (1729) Virginia Woolf – Street Haunting: A London Adventure (1930) John McPhee – The Search for Marvin Gardens (1972) Joan Didion – The White Album (1968-1978) Eudora Welty – The Little Store (1978) Phillip Lopate – Against Joie de Vivre (1989)

On 2 lists Sei Shonagon – Hateful Things (from The Pillow Book ) (1002) Yoshida Kenko – Essays in Idleness (1332) Michel de Montaigne – On Some Verses of Virgil (1580) Robert Burton – Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) John Milton – Areopagitica (1644) William Hazlitt – On Going a Journey (1822) Charles Lamb – The Superannuated Man (1823) Henry David Thoreau – Civil Disobedience (1849) Henry David Thoreau – Where I Lived, and What I Lived For (from Walden ) (1854) Henry David Thoreau – Economy (from Walden ) (1854) Henry David Thoreau – Walking (1861) Robert Louis Stevenson – The Lantern-Bearers (1888) Zora Neale Hurston – How It Feels to Be Colored Me (1928) George Orwell – A Hanging (1931) Junichiro Tanizaki – In Praise of Shadows (1933) Fernando Pessoa – The Book of Disquiet (1935) James Agee and Walker Evans – Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) Simone Weil – On Human Personality (1943) M.F.K. Fisher – The Flaw (1943) Vladimir Nabokov – Speak, Memory (1951, revised 1966) Mary McCarthy – Artists in Uniform: A Story (1953) E.B. White – Goodbye to Forty-Eighth Street (1957) Martin Luther King, Jr. – Letter from Birmingham Jail (1963) Joseph Mitchell – Joe Gould’s Secret (1964) Susan Sontag – Against Interpretation (1966) Edward Hoagland – The Courage of Turtles (1970) Annie Dillard – Seeing (from Pilgrim at Tinker Creek ) (1974) Maxine Hong Kingston – No Name Woman (from The Woman Warrior ) (1976) Roland Barthes – Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (1982) Annie Dillard – Living Like Weasels (1982) Gloria E. Anzaldúa – How to Tame a Wild Tongue (1987) Italo Calvino – Exactitude (1988) Richard Rodriguez – Late Victorians (1990) David Wojnarowicz – Being Queer in America: A Journal of Disintegration (1991) Seymour Krim – To My Brothers & Sisters in the Failure Business (1991) Anne Carson – The Anthropology of Water (1995) Susan Sontag – Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) Etel Adnan – In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country (2005) Paul LaFarge – Destroy All Monsters (2006) Brian Doyle – Joyas Voladoras (2012)

Share this:

How to Write a History Essay, According to a History Professor

- History classes almost always include an essay assignment.

- Focus your paper by asking a historical question and then answering it.

- Your introduction can make or break your essay.

- When in doubt, reach out to your history professor for guidance.

In nearly every history class, you’ll need to write an essay . But what if you’ve never written a history paper? Or what if you’re a history major who struggles with essay questions?

I’ve written over 100 history papers between my undergraduate education and grad school — and I’ve graded more than 1,500 history essays, supervised over 100 capstone research papers, and sat on more than 10 graduate thesis committees.

Here’s my best advice on how to write a history paper.

How to Write a History Essay in 6 Simple Steps

You have the prompt or assignment ready to go, but you’re stuck thinking, “How do I start a history essay?” Before you start typing, take a few steps to make the process easier.

Whether you’re writing a three-page source analysis or a 15-page research paper , understanding how to start a history essay can set you up for success.

Step 1: Understand the History Paper Format

You may be assigned one of several types of history papers. The most common are persuasive essays and research papers. History professors might also ask you to write an analytical paper focused on a particular source or an essay that reviews secondary sources.

Spend some time reading the assignment. If it’s unclear what type of history paper format your professor wants, ask.

Regardless of the type of paper you’re writing, it will need an argument. A strong argument can save a mediocre paper — and a weak argument can harm an otherwise solid paper.

Your paper will also need an introduction that sets up the topic and argument, body paragraphs that present your evidence, and a conclusion .

Step 2: Choose a History Paper Topic

If you’re lucky, the professor will give you a list of history paper topics for your essay. If not, you’ll need to come up with your own.

What’s the best way to choose a topic? Start by asking your professor for recommendations. They’ll have the best ideas, and doing this can save you a lot of time.

Alternatively, start with your sources. Most history papers require a solid group of primary sources. Decide which sources you want to use and craft a topic around the sources.

Finally, consider starting with a debate. Is there a pressing question your paper can address?

Before continuing, run your topic by your professor for feedback. Most students either choose a topic so broad it could be a doctoral dissertation or so narrow it won’t hit the page limit. Your professor can help you craft a focused, successful topic. This step can also save you a ton of time later on.

Step 3: Write Your History Essay Outline

It’s time to start writing, right? Not yet. You’ll want to create a history essay outline before you jump into the first draft.

You might have learned how to outline an essay back in high school. If that format works for you, use it. I found it easier to draft outlines based on the primary source quotations I planned to incorporate in my paper. As a result, my outlines looked more like a list of quotes, organized roughly into sections.

As you work on your outline, think about your argument. You don’t need your finished argument yet — that might wait until revisions. But consider your perspective on the sources and topic.

Jot down general thoughts about the topic, and formulate a central question your paper will answer. This planning step can also help to ensure you aren’t leaving out key material.

Step 4: Start Your Rough Draft

It’s finally time to start drafting! Some students prefer starting with the body paragraphs of their essay, while others like writing the introduction first. Find what works best for you.

Use your outline to incorporate quotes into the body paragraphs, and make sure you analyze the quotes as well.

When drafting, think of your history essay as a lawyer would a case: The introduction is your opening statement, the body paragraphs are your evidence, and the conclusion is your closing statement.

When writing a conclusion for a history essay, make sure to tie the evidence back to your central argument, or thesis statement .

Don’t stress too much about finding the perfect words for your first draft — you’ll have time later to polish it during revisions. Some people call this draft the “sloppy copy.”

Step 5: Revise, Revise, Revise

Once you have a first draft, begin working on the second draft. Revising your paper will make it much stronger and more engaging to read.

During revisions, look for any errors or incomplete sentences. Track down missing footnotes, and pay attention to your argument and evidence. This is the time to make sure all your body paragraphs have topic sentences and that your paper meets the requirements of the assignment.

If you have time, take a day off from the paper and come back to it with fresh eyes. Then, keep revising.

Step 6: Spend Extra Time on the Introduction

No matter the length of your paper, one paragraph will determine your final grade: the introduction.

The intro sets up the scope of your paper, the central question you’ll answer, your approach, and your argument.

In a short paper, the intro might only be a single paragraph. In a longer paper, it’s usually several paragraphs. The introduction for my doctoral dissertation, for example, was 28 pages!

Use your introduction wisely. Make a strong statement of your argument. Then, write and rewrite your argument until it’s as clear as possible.

If you’re struggling, consider this approach: Figure out the central question your paper addresses and write a one-sentence answer to the question. In a typical 3-to-5-page paper, my shortcut argument was to say “X happened because of A, B, and C.” Then, use body paragraphs to discuss and analyze A, B, and C.

Tips for Taking Your History Essay to the Next Level

You’ve gone through every step of how to write a history essay and, somehow, you still have time before the due date. How can you take your essay to the next level? Here are some tips.

- Talk to Your Professor: Each professor looks for something different in papers. Some prioritize the argument, while others want to see engagement with the sources. Ask your professor what elements they prioritize. Also, get feedback on your topic, your argument, or a draft. If your professor will read a draft, take them up on the offer.

- Write a Question — and Answer It: A strong history essay starts with a question. “Why did Rome fall?” “What caused the Protestant Reformation?” “What factors shaped the civil rights movement?” Your question can be broad, but work on narrowing it. Some examples: “What role did the Vandal invasions play in the fall of Rome?” “How did the Lollard movement influence the Reformation?” “How successful was the NAACP legal strategy?”

- Hone Your Argument: In a history paper, the argument is generally about why or how historical events (or historical changes) took place. Your argument should state your answer to a historical question. How do you know if you have a strong argument? A reasonable person should be able to disagree. Your goal is to persuade the reader that your interpretation has the strongest evidence.

- Address Counterarguments: Every argument has holes — and every history paper has counterarguments. Is there evidence that doesn’t fit your argument? Address it. Your professor knows the counterarguments, so it’s better to address them head-on. Take your typical five-paragraph essay and add a paragraph before the conclusion that addresses these counterarguments.

- Ask Someone to Read Your Essay: If you have time, asking a friend or peer to read your essay can help tremendously, especially when you can ask someone in the class. Ask your reader to point out anything that doesn’t make sense, and get feedback on your argument. See whether they notice any counterarguments you don’t address. You can later repay the favor by reading one of their papers.

Congratulations — you finished your history essay! When your professor hands back your paper, be sure to read their comments closely. Pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses in your paper. And use this experience to write an even stronger essay next time.

Subscription Offers

Give a Gift

How To Write a Good History Essay

The former editor of History Review Robert Pearce gives his personal view.

First of all we ought to ask, What constitutes a good history essay? Probably no two people will completely agree, if only for the very good reason that quality is in the eye – and reflects the intellectual state – of the reader. What follows, therefore, skips philosophical issues and instead offers practical advice on how to write an essay that will get top marks.

Witnesses in court promise to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. All history students should swear a similar oath: to answer the question, the whole question and nothing but the question. This is the number one rule. You can write brilliantly and argue a case with a wealth of convincing evidence, but if you are not being relevant then you might as well be tinkling a cymbal. In other words, you have to think very carefully about the question you are asked to answer. Be certain to avoid the besetting sin of those weaker students who, fatally, answer the question the examiners should have set – but unfortunately didn’t. Take your time, look carefully at the wording of the question, and be certain in your own mind that you have thoroughly understood all its terms.

If, for instance, you are asked why Hitler came to power, you must define what this process of coming to power consisted of. Is there any specific event that marks his achievement of power? If you immediately seize on his appointment as Chancellor, think carefully and ask yourself what actual powers this position conferred on him. Was the passing of the Enabling Act more important? And when did the rise to power actually start? Will you need to mention Hitler’s birth and childhood or the hyperinflation of the early 1920s? If you can establish which years are relevant – and consequently which are irrelevant – you will have made a very good start. Then you can decide on the different factors that explain his rise.

Or if you are asked to explain the successes of a particular individual, again avoid writing the first thing that comes into your head. Think about possible successes. In so doing, you will automatically be presented with the problem of defining ‘success’. What does it really mean? Is it the achievement of one’s aims? Is it objective (a matter of fact) or subjective (a matter of opinion)? Do we have to consider short-term and long-term successes? If the person benefits from extraordinary good luck, is that still a success? This grappling with the problem of definition will help you compile an annotated list of successes, and you can then proceed to explain them, tracing their origins and pinpointing how and why they occurred. Is there a key common factor in the successes? If so, this could constitute the central thrust of your answer.

Save 35% with a student subscription to History Today

The key word in the above paragraphs is think . This should be distinguished from remembering, daydreaming and idly speculating. Thinking is rarely a pleasant undertaking, and most of us contrive to avoid it most of the time. But unfortunately there’s no substitute if you want to get the top grade. So think as hard as you can about the meaning of the question, about the issues it raises and the ways you can answer it. You have to think and think hard – and then you should think again, trying to find loopholes in your reasoning. Eventually you will almost certainly become confused. Don’t worry: confusion is often a necessary stage in the achievement of clarity. If you get totally confused, take a break. When you return to the question, it may be that the problems have resolved themselves. If not, give yourself more time. You may well find that decent ideas simply pop into your conscious mind at unexpected times.

You need to think for yourself and come up with a ‘bright idea’ to write a good history essay. You can of course follow the herd and repeat the interpretation given in your textbook. But there are problems here. First, what is to distinguish your work from that of everybody else? Second, it’s very unlikely that your school text has grappled with the precise question you have been set.

The advice above is relevant to coursework essays. It’s different in exams, where time is limited. But even here, you should take time out to do some thinking. Examiners look for quality rather than quantity, and brevity makes relevance doubly important. If you get into the habit of thinking about the key issues in your course, rather than just absorbing whatever you are told or read, you will probably find you’ve already considered whatever issues examiners pinpoint in exams.

The Vital First Paragraph

Every part of an essay is important, but the first paragraph is vital. This is the first chance you have to impress – or depress – an examiner, and first impressions are often decisive. You might therefore try to write an eye-catching first sentence. (‘Start with an earthquake and work up to a climax,’ counselled the film-maker Cecil B. De Mille.) More important is that you demonstrate your understanding of the question set. Here you give your carefully thought out definitions of the key terms, and here you establish the relevant time-frame and issues – in other words, the parameters of the question. Also, you divide the overall question into more manageable sub-divisions, or smaller questions, on each of which you will subsequently write a paragraph. You formulate an argument, or perhaps voice alternative lines of argument, that you will substantiate later in the essay. Hence the first paragraph – or perhaps you might spread this opening section over two paragraphs – is the key to a good essay.

On reading a good first paragraph, examiners will be profoundly reassured that its author is on the right lines, being relevant, analytical and rigorous. They will probably breathe a sign of relief that here is one student at least who is avoiding the two common pitfalls. The first is to ignore the question altogether. The second is to write a narrative of events – often beginning with the birth of an individual – with a half-hearted attempt at answering the question in the final paragraph.

Middle Paragraphs

Philip Larkin once said that the modern novel consists of a beginning, a muddle and an end. The same is, alas, all too true of many history essays. But if you’ve written a good opening section, in which you’ve divided the overall question into separate and manageable areas, your essay will not be muddled; it will be coherent.

It should be obvious, from your middle paragraphs, what question you are answering. Indeed it’s a good test of an essay that the reader should be able to guess the question even if the title is covered up. So consider starting each middle paragraph will a generalisation relevant to the question. Then you can develop this idea and substantiate it with evidence. You must give a judicious selection of evidence (i.e. facts and quotations) to support the argument you are making. You only have a limited amount of space or time, so think about how much detail to give. Relatively unimportant background issues can be summarised with a broad brush; your most important areas need greater embellishment. (Do not be one of those misguided candidates who, unaccountably, ‘go to town’ on peripheral areas and gloss over crucial ones.)

The regulations often specify that, in the A2 year, students should be familiar with the main interpretations of historians. Do not ignore this advice. On the other hand, do not take historiography to extremes, so that the past itself is virtually ignored. In particular, never fall into the trap of thinking that all you need are sets of historians’ opinions. Quite often in essays students give a generalisation and back it up with the opinion of an historian – and since they have formulated the generalisation from the opinion, the argument is entirely circular, and therefore meaningless and unconvincing. It also fatuously presupposes that historians are infallible and omniscient gods. Unless you give real evidence to back up your view – as historians do – a generalisation is simply an assertion. Middle paragraphs are the place for the real substance of an essay, and you neglect this at your peril.

Final Paragraph

If you’ve been arguing a case in the body of an essay, you should hammer home that case in the final paragraph. If you’ve been examining several alternative propositions, now is the time to say which one is correct. In the middle paragraph you are akin to a barrister arguing a case. Now, in the final paragraph, you are the judge summing up and pronouncing the verdict.

It’s as well to keep in mind what you should not be doing. Do not introduce lots of fresh evidence at this stage, though you can certainly introduce the odd extra fact that clinches your case. Nor should you go on to the ‘next’ issue. If your question is about Hitler coming to power, you should not end by giving a summary of what he did once in power. Such an irrelevant ending will fail to win marks. Remember the point about answering ‘nothing but the question’? On the other hand, it may be that some of the things Hitler did after coming to power shed valuable light on why he came to power in the first place. If you can argue this convincingly, all well and good; but don’t expect the examiner to puzzle out relevance. Examiners are not expected to think; you must make your material explicitly relevant.

Final Thoughts

A good essay, especially one that seems to have been effortlessly composed, has often been revised several times; and the best students are those who are most selfcritical. Get into the habit of criticising your own first drafts, and never be satisfied with second-best efforts. Also, take account of the feedback you get from teachers. Don’t just look at the mark your essay gets; read the comments carefully. If teachers don’t advise how to do even better next time, they are not doing their job properly.

Relevance is vital in a good essay, and so is evidence marshalled in such a way that it produces a convincing argument. But nothing else really matters. The paragraph structure recommended above is just a guide, nothing more, and you can write a fine essay using a very different arrangement of material. Similarly, though it would be excellent if you wrote in expressive, witty and sparklingly provocative prose, you can still get top marks even if your essay is serious, ponderous and even downright dull.

There are an infinite number of ways to write an essay because any form of writing is a means of self-expression. Your essay will be unique because you are unique: it’s up to you to ensure that it’s uniquely good, not uniquely mediocre.

Robert Pearce is the editor of History Review .

Popular articles

Books of the Year 2024: Part 1

Who was Thorkell the Tall?

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

In this blog, you will find a range of history essay examples that showcase the best practices in history essay writing. Read on to find useful examples. On This Page. Sample History Essays. Explore our collection of excellent history paper examples about various history essay topics. Download the pdf examples for free and read to get ...

In other words, writing history isn't about choosing sides, but these SIDES can assist you in arriving at a clear, well-supported perspective on your topic. ... Every type of writing has conventions and best practices that writers should follow. That said, there is no one way to write a history paper. Use your own voice, follow your teacher ...

Guide for Writing in History About Writing in History Common Approaches to Historical Writing Historical writing should always be analytic, moving beyond simple description. Critical historical analysis examines relationships and distinctions that are not immediately obvious. Good historical writers carefully evaluate and interpret their ...

Historical essay writing is based upon the thesis. A thesis is a statement, an argument which will be presented by the writer. The thesis is in effect, your position, your particular interpretation, your way of seeing a problem. Resist the temptation, which many students have, to think of a thesis as simply "restating" an instructor's question.

(a.k.a., Making) History At first glance, writing about history can seem like an overwhelming task. History's subject matter is immense, encompassing all of human affairs in the recorded past — up until the moment, that is, that you started reading this guide. Because no one person can possibly consult all of these records, no work of ...

To achieve the correct structure for your argument, it is crucial to understand the separate parts that make up a written essay. If you understand how each part works and fits into the overall essay, you are well on the way to creating a great assessment piece. Most essays will require you to write: 1 Introduction Paragraph; 3 Body Paragraphs

A reader suggested I create a meta-list of the best essays of all time, so I did. I found over 12 best essays lists and several essay anthologies and combined the essays into one meta-list. ... Best Athletes - By Sport; History. Timeline of Human History I: Prehistory to 1499. Timeline of Human History II: 1500-1799;

In approaching writing in History & Literature, the best way to begin is to work inductively, beginning with small details found in your text. Rather than starting with a broad premise and looking for details in the text to support that premise, begin with the details in the text and work out from there to make a larger claim. While

Here's my best advice on how to write a history paper. How to Write a History Essay in 6 Simple Steps. You have the prompt or assignment ready to go, but you're stuck thinking, "How do I start a history essay?" ... Write a Question — and Answer It: A strong history essay starts with a question. "Why did Rome fall?" "What caused ...

A good essay, especially one that seems to have been effortlessly composed, has often been revised several times; and the best students are those who are most selfcritical. Get into the habit of criticising your own first drafts, and never be satisfied with second-best efforts. Also, take account of the feedback you get from teachers.