How to Format a College Essay: Step-by-Step Guide

Mark Twain once said, “I like a good story well told. That’s the reason I am sometimes forced to tell them myself.”

At College Essay Guy, we too like good stories well told.

The problem is that sometimes students have really good stories … that just aren’t well told.

They have the seed of an idea and the makings of a great story, but the essay formatting or structure is all over the place.

Which can lead a college admissions reader to see you as disorganized. And your essay doesn’t make as much of an impact as it could.

So, if you’re here, you’re probably wondering:

Is there any kind of required format for a college essay? How do I structure my essay?

And maybe what’s the difference?

Good news: That’s what this post answers.

First, let’s go over a few basic questions students often have when trying to figure out how to format their essay.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- College essay format guidelines

- How to brainstorm and structure a college essay topic

- Recommended brainstorming examples

- Example college essay: The “Burying Grandma” essay

College Essay Format Guidelines

Should I title my college essay?

You don’t need one. In the vast majority of cases, students we work with don’t use titles. The handful of times they have, they’ve done so because the title allows for a subtle play on words or reframing of the essay as a whole. So don’t feel any pressure to include one—they’re purely optional.

Should I indent or us paragraph breaks in my college essay?

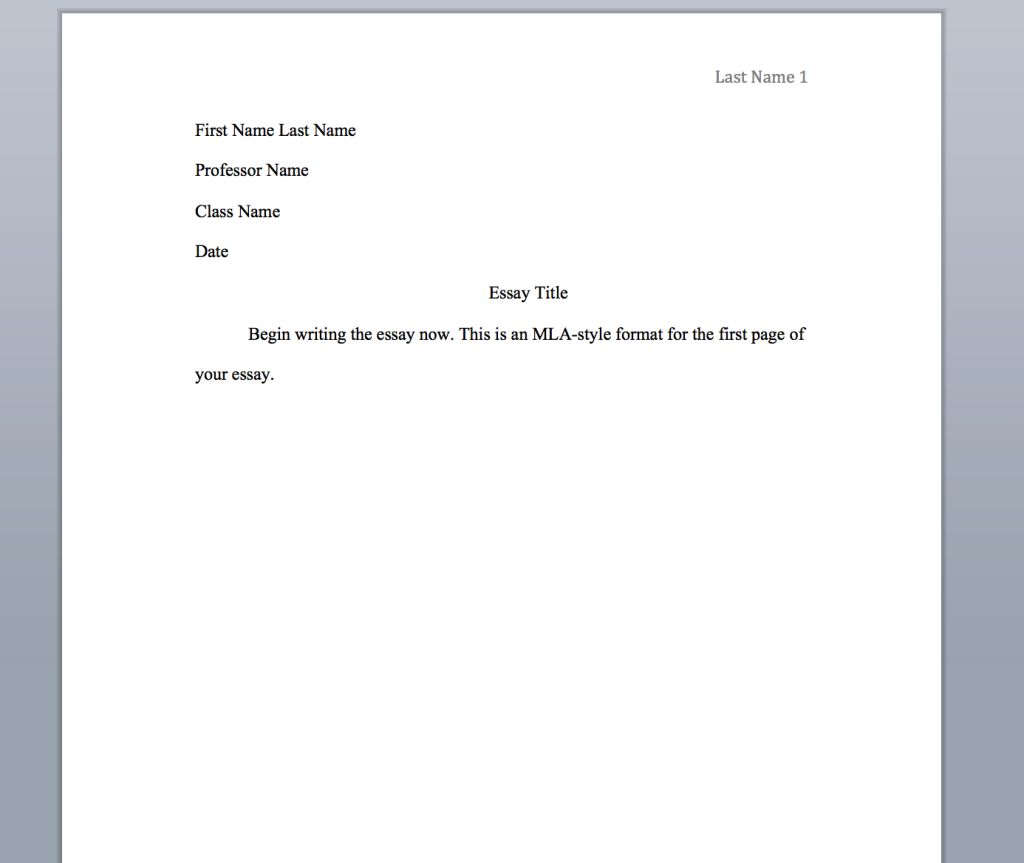

Either. Just be consistent. The exception here is if you’re pasting into a box that screws up your formatting—for example, if, when you copy your essay into the box, your indentations are removed, go with paragraph breaks. (And when you get to college, be sure to check what style guide you should be following: Chicago, APA, MLA, etc., can all take different approaches to formatting, and different fields have different standards.)

How many paragraphs should a college essay be?

Personal statements are not English essays. They don’t need to be 5 paragraphs with a clear, argumentative thesis in the beginning and a conclusion that sums everything up. So feel free to break from that. How many paragraphs are appropriate for a college essay? Within reason, it’s up to you. We’ve seen some great personal statements that use 4 paragraphs, and some that use 8 or more (especially if you have dialogue—yes, dialogue is OK too!).

How long should my college essay be?

The good news is that colleges and the application systems they use will usually give you specific word count maximums. The most popular college application systems, like the Common Application and Coalition Application, will give you a maximum of 650 words for your main personal statement, and typically less than that for school-specific supplemental essays . Other systems will usually specify the maximum word count—the UC PIQs are 350 max, for example. If they don’t specify this clearly in the application systems or on their website (and be sure to do some research), you can email them to ask! They don’t bite.

So should you use all that space? We generally recommend it. You likely have lots to share about your life, so we think that not using all the space they offer to tell your story might be a missed opportunity. While you don’t have to use every last word, aim to use most of the words they give you. But don’t just fill the space if what you’re sharing doesn’t add to the overall story you’re telling.

There are also some applications or supplementals with recommended word counts or lengths. For example, Georgetown says things like “approx. 1 page,” and UChicago doesn’t have a limit, but recommends aiming for 650ish for the extended essay, and 250-500 for the “Why us?”

You can generally apply UChicago’s recommendations to other schools that don’t give you a limit: If it’s a “Why Major” supplement, 650 is probably plenty, and for other supplements, 250-500 is a good target to shoot for. If you go over those, that can be fine, just be sure you’re earning that word count (as in, not rambling or being overly verbose). Your readers are humans. If you send them a tome, their attention could drift.

Regarding things like italics and bold

Keep in mind that if you’re pasting text into a box, it may wipe out your formatting. So if you were hoping to rely on italics or bold for some kind of emphasis, double check if you’ll be able to. (And in general, try to use sentence structure and phrasing to create that kind of emphasis anyway, rather than relying on bold or italics—doing so will make you a better writer.)

Regarding font type, size, and color

Keep it simple and standard. Regarding font type, things like Times New Roman or Georgia (what this is written in) won’t fail you. Just avoid things like Comic Sans or other informal/casual fonts.

Size? 11- or 12-point is fine.

Color? Black.

Going with something else with the above could be a risk, possibly a big one, for fairly little gain. Things like a wacky font or text color could easily feel gimmicky to a reader.

To stand out with your writing, take some risks in what you write about and the connections and insights you make.

If you’re attaching a doc (rather than pasting)

If you are attaching a document rather than pasting into a text box, all the above still applies. Again, we’d recommend sticking with standard fonts and sizes—Times New Roman, 12-point is a standard workhorse. You can probably go with 1.5 or double spacing. Standard margins.

Basically, show them you’re ready to write in college by using the formatting you’ll normally use in college.

Is there a college essay template I can use?

Depends on what you’re asking for. If, by “template,” you’re referring to formatting … see above.

But if you mean a structural template ... not exactly. There is no one college essay template to follow. And that’s a good thing.

That said, we’ve found that there are two basic structural approaches to writing college essays that can work for every single prompt we’ve seen. (Except for lists. Because … they’re lists.)

Below we’ll cover those two essay structures we love, but you’ll see how flexible these are—they can lead to vastly different essays. You can also check out a few sample essays to get a sense of structure and format (though we’d recommend doing some brainstorming and outlining to think of possible topics before you look at too many samples, since they can poison the well for some people).

Let’s dig in.

STEP 1: HOW TO BRAINSTORM AN AMAZING ESSAY TOPIC

We’ll talk about structure and topic together. Why? Because one informs the other.

(And to clarify: When we say, “topic,” we mean the theme or focus of your essay that you use to show who you are and what you value. The “topic” of your college essay is always ultimately you.)

We think there are two basic structural approaches that can work for any college essay. Not that these are the only two options—rather, that these can work for any and every prompt you’ll have to write for.

Which structural approach you use depends on your answer to this question (and its addendum): Do you feel like you’ve faced significant challenges in your life … or not so much? (And do you want to write about them?)

If yes (to both), you’ll most likely want to use Narrative Structure . If no (to either), you’ll probably want to try Montage Structure .

So … what are those structures? And how do they influence your topic?

Narrative Structure is classic storytelling structure. You’ve seen this thousands of times—assuming you read, and watch movies and TV, and tell stories with friends and family. If you don’t do any of these things, this might be new. Otherwise, you already know this. You may just not know you know it. Narrative revolves around a character or characters (for a college essay, that’s you) working to overcome certain challenges, learning and growing, and gaining insight. For a college essay using Narrative Structure, you’ll focus the word count roughly equally on a) Challenges You Faced, b) What You Did About Them, and c) What You Learned (caveat that those sections can be somewhat interwoven, especially b and c). Paragraphs and events are connected causally.

You’ve also seen montages before. But again, you may not know you know. So: A montage is a series of thematically connected things, frequently images. You’ve likely seen montages in dozens and dozens of films before—in romantic comedies, the “here’s the couple meeting and dating and falling in love” montage; in action movies, the classic “training” montage. A few images tell a larger story. In a college essay, you could build a montage by using a thematic thread to write about five different pairs of pants that connect to different sides of who you are and what you value. Or different but connected things that you love and know a lot about (like animals, or games). Or entries in your Happiness Spreadsheet .

How does structure play into a great topic?

We believe a montage essay (i.e., an essay NOT about challenges) is more likely to stand out if the topic or theme of the essay is:

X. Elastic (i.e., something you can connect to variety of examples, moments, or values) Y. Uncommon (i.e., something other students probably aren’t writing about)

We believe that a narrative essay is more likely to stand out if it contains:

X. Difficult or compelling challenges Y. Insight

These aren’t binary—rather, each exists on a spectrum.

“Elastic” will vary from person to person. I might be able to connect mountain climbing to family, history, literature, science, social justice, environmentalism, growth, insight … and someone else might not connect it to much of anything. Maybe trees?

“Uncommon” —every year, thousands of students write about mission trips, sports, or music. It’s not that you can’t write about these things, but it’s a lot harder to stand out.

“Difficult or compelling challenges” can be put on a spectrum, with things like getting a bad grade or not making a sports team on the weaker end, and things like escaping war or living homeless for three years on the stronger side. While you can possibly write a strong essay about a weaker challenge, it’s really hard to do so.

“Insight” is the answer to the question “so what?” A great insight is likely to surprise the reader a bit, while a so-so insight likely won’t. (Insight is something you’ll develop in an essay through the writing process, rather than something you’ll generally know ahead of time for a topic, but it’s useful to understand that some topics are probably easier to pull insights from than others.)

To clarify, you can still write a great montage with a very common topic, or a narrative that offers so-so insights. But the degree of difficulty goes up. Probably way up.

With that in mind, how do you brainstorm possible topics that are on the easier-to-stand-out-with side of the spectrum?

Brainstorming exercises

Spend about 10 minutes (minimum) on each of these exercises.

Values Exercise

Essence Objects Exercise

21 Details Exercise

Everything I Want Colleges To Know About Me Exercise

Feelings and Needs Exercise

If you feel like you already have your topic, and you just want to know how to make it better…

Still do those exercises.

Maybe what you have is the best topic for you. And if you are incredibly super sure, you can skip ahead. But if you’re not sure this topic helps you communicate your deepest stories, spend a little time on the exercises above. As a bonus, even if you end up going with what you already had (though please be wary of the sunk cost fallacy ), all that brainstorming will be useful when you write your supplemental essays .

The Feelings and Needs Exercise in particular is great for brainstorming Narrative Structure, connecting story events in a causal way (X led to Y led to Z). The Essence Objects, 21 Details, Everything I Want Colleges to Know exercises can lead to interesting thematic threads for Montage Structure (P, Q, and R are all connected because, for example, they’re all qualities of a great endodontist). But all of them are useful for both structural approaches. Essence objects can help a narrative come to life. One paragraph in a montage could focus on a challenge and how you overcame it.

The Values Exercise is a cornerstone of both—regardless of whether you use narrative or montage, we should get a sense of some of your core values through your essays.

How (and why) to outline your college essay to use a good structure

While not every professional writer knows exactly how a story will end when they start writing, they also have months (or years) to craft it, and they may throw major chunks or whole drafts away. You probably don’t want to throw away major chunks or whole drafts. So you should outline.

Use the brainstorming exercises from earlier to decide on your most powerful topics and what structure (narrative or montage) will help you best tell your story.

Then, outline.

For a narrative, use the Feelings and Needs Exercise, and build clear bullet points for the Challenges + Effects, What I Did About It, and What I Learned. Those become your outline.

Yeah, that simple.

For a montage, outline 4-7 ways your thread connects to different values through different experiences, and if you can think of them, different lessons and insights (though these you might have to develop later, during the writing process). For example, how auto repair connects to family, literature, curiosity, adventure, and personal growth (through different details and experiences).

Here are some good example outlines:

Narrative outline (developed from the Feelings and Needs Exercise)

Challenges:

Domestic abuse (physical and verbal)

Controlling father/lack of freedom

Sexism/bias

Prevented from pursuing opportunities

Cut off from world/family

Lack of sense of freedom/independence

Faced discrimination

What I Did About It:

Pursued my dreams

Traveled to Egypt, London, and Paris alone

Challenged stereotypes

Explored new places and cultures

Developed self-confidence, independence, and courage

Grew as a leader

Planned events

What I Learned:

Inspired to help others a lot more

Learned about oppression, and how to challenge oppressive norms

Became closer with mother, somewhat healed relationship with father

Need to feel free

And here’s the essay that became: “ Easter ”

Montage outline:

Thread: Home

Values: Family, tradition, literature

Ex: “Tailgate Special,” discussions w/family, reading Nancy Drew

Perception, connection to family

Chinese sword dance

Values: Culture/heritage, meticulousness, dedication, creativity

Ex: Notebook, formations/choreography

Nuances of culture, power of connection

Values: Science/chemistry, curiosity

Synthesizing plat nanoparticles

Joy of discovery, redefining expectations

Governor’s School

Values: Exploration, personal growth

Knitting, physics, politics, etc.

Importance of exploring beyond what I know/am used to, taking risks

And here’s the essay that became: “ Home ”

When to scrap what you have and start over

Ultimately, you can’t know for sure if a topic will work until you try a draft or two. And maybe it’ll be great. But keep that sunk cost fallacy in mind, and be open to trying other things.

If you’re down the rabbit hole with a personal statement topic and just aren’t sure about it, the first step you should take is to ask for feedback. Find a partner who can help you examine it without the attachment to all the emotion (anxiety, worry, or fear) you might have built up around it.

Have them help you walk through The Great College Essay Test to make sure your essay is doing its job. If it isn’t yet, does it seem like this topic has the potential to? Or would other topics allow you to more fully show a college who you are and what you bring to the table?

Because that’s your goal. Format and structure are just tools to get you there.

Down the Road

Before we analyze some sample essays, bookmark this page, so that once you’ve gone through several drafts of your own essay, come back and take The Great College Essay Test to make sure your essay is doing its job. The job of the essay, simply put, is to demonstrate to a college that you’ll make valuable contributions in college and beyond. We believe these four qualities are essential to a great essay:

Core values (showing who you are through what you value)

Vulnerability (helps a reader feel connected to you)

Insight (aka “so what” moments)

Craft (clear structure, refined language, intentional choices)

To test what values are coming through, read your essay aloud to someone who knows you and ask:

Which values are clearly coming through the essay?

Which values are kind of there but could be coming through more clearly?

Which values could be coming through and were opportunities missed?

To know if you’re being vulnerable in your essay, ask:

Now that you’ve heard my story, do you feel closer to me?

What did you learn about me that you didn’t already know?

To search for “so what” moments of insight, review the claims you’re making in your essay. Are you reflecting on what these moments and experiences taught you? How have they changed you? Are you making common or (hopefully) uncommon connections? The uncommon connections are often made up of insights that are unusual or unexpected. (For more on how to test for this, click The Great College Essay Test link above.)

Craft comes through the sense that each paragraph, each sentence, each word is a carefully considered choice. That the author has spent time revising and refining. That the essay is interesting and succinct. How do you test this? For each paragraph, each sentence, each word, ask: Do I need this? (Huge caveat: Please avoid neurotic perfectionism here. We’re just asking you to be intentional with your language.)

Still feeling you haven’t found your topic? Here’s a list of 100 Brave and Interesting Questions . Read these and try freewriting on a few. See where they lead.

Finally, here’s an ...

Example College Essay Format Analysis: The “Burying Grandma” Essay

To see how the Narrative Essay structure works, check out the essay below, which was written for the Common App "Topic of your choice" prompt. You might try reading it here first before reading the paragraph-by-paragraph breakdown below.

They covered the precious mahogany coffin with a brown amalgam of rocks, decomposed organisms, and weeds. It was my turn to take the shovel, but I felt too ashamed to dutifully send her off when I had not properly said goodbye. I refused to throw dirt on her. I refused to let go of my grandmother, to accept a death I had not seen coming, to believe that an illness could not only interrupt, but steal a beloved life.

The author begins by setting up the Challenges + Effects (you’ve maybe heard of this referred to in narrative as the Inciting Incident). This moment also sets up some of her needs: growth and emotional closure, to deal with it and let go/move on. Notice the way objects like the shovel help bring an essay to life, and can be used for symbolic meaning. That object will also come back later.

When my parents finally revealed to me that my grandmother had been battling liver cancer, I was twelve and I was angry--mostly with myself. They had wanted to protect me--only six years old at the time--from the complex and morose concept of death. However, when the end inevitably arrived, I wasn’t trying to comprehend what dying was; I was trying to understand how I had been able to abandon my sick grandmother in favor of playing with friends and watching TV. Hurt that my parents had deceived me and resentful of my own oblivion, I committed myself to preventing such blindness from resurfacing.

In the second paragraph, she flashes back to give us some context of what things were like leading up to these challenges (i.e., the Status Quo), which helps us understand her world. It also helps us to better understand the impact of her grandmother’s death and raises a question: How will she prevent such blindness from resurfacing?

I became desperately devoted to my education because I saw knowledge as the key to freeing myself from the chains of ignorance. While learning about cancer in school I promised myself that I would memorize every fact and absorb every detail in textbooks and online medical journals. And as I began to consider my future, I realized that what I learned in school would allow me to silence that which had silenced my grandmother. However, I was focused not with learning itself, but with good grades and high test scores. I started to believe that academic perfection would be the only way to redeem myself in her eyes--to make up for what I had not done as a granddaughter.

In the third paragraph, she starts shifting into the What I Did About It aspect, and takes off at a hundred miles an hour … but not quite in the right direction yet. What does that mean? She pursues things that, while useful and important in their own right, won’t actually help her resolve her conflict. This is important in narrative—while it can be difficult, or maybe even scary, to share ways we did things wrong, that generally makes for a stronger story. Think of it this way: You aren’t really interested in watching a movie in which a character faces a challenge, knows what to do the whole time, so does it, the end. We want to see how people learn and change and grow.

Here, the author “Raises the Stakes” because we as readers sense intuitively (and she is giving us hints) that this is not the way to get over her grandmother’s death.

However, a simple walk on a hiking trail behind my house made me open my own eyes to the truth. Over the years, everything--even honoring my grandmother--had become second to school and grades. As my shoes humbly tapped against the Earth, the towering trees blackened by the forest fire a few years ago, the faintly colorful pebbles embedded in the sidewalk, and the wispy white clouds hanging in the sky reminded me of my small though nonetheless significant part in a larger whole that is humankind and this Earth. Before I could resolve my guilt, I had to broaden my perspective of the world as well as my responsibilities to my fellow humans.

There’s some nice evocative detail in here that helps draw us into her world and experience.

Structurally, there are elements of What I Did About It and What I Learned in here (again, they will often be somewhat interwoven). This paragraph gives us the Turning Point/Moment of Truth. She begins to understand how she was wrong. She realizes she needs perspective. But how? See next paragraph ...

Volunteering at a cancer treatment center has helped me discover my path. When I see patients trapped in not only the hospital but also a moment in time by their diseases, I talk to them. For six hours a day, three times a week, Ivana is surrounded by IV stands, empty walls, and busy nurses that quietly yet constantly remind her of her breast cancer. Her face is pale and tired, yet kind--not unlike my grandmother’s. I need only to smile and say hello to see her brighten up as life returns to her face. Upon our first meeting, she opened up about her two sons, her hometown, and her knitting group--no mention of her disease. Without even standing up, the three of us—Ivana, me, and my grandmother--had taken a walk together.

In the second-to-last paragraph, we see how she takes further action, and some of what she learns from her experiences: Volunteering at the local hospital helps her see her larger place in the world.

Cancer, as powerful and invincible as it may seem, is a mere fraction of a person’s life. It’s easy to forget when one’s mind and body are so weak and vulnerable. I want to be there as an oncologist to remind them to take a walk once in a while, to remember that there’s so much more to life than a disease. While I physically treat their cancer, I want to lend patients emotional support and mental strength to escape the interruption and continue living. Through my work, I can accept the shovel without burying my grandmother’s memory.

The final paragraph uses what we call the “bookend” technique by bringing us back to the beginning, but with a change—she’s a different, slightly wiser person than she was. This helps us put a frame around her growth.

… A good story well told . That’s your goal.

Hopefully, you now have a better sense of how to make that happen.

For more resources, check out our College Application Hub .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Forums Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Format an Essay

Last Updated: July 29, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Carrie Adkins, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Aly Rusciano . Carrie Adkins is the cofounder of NursingClio, an open access, peer-reviewed, collaborative blog that connects historical scholarship to current issues in gender and medicine. She completed her PhD in American History at the University of Oregon in 2013. While completing her PhD, she earned numerous competitive research grants, teaching fellowships, and writing awards. There are 15 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 98,061 times.

You’re opening your laptop to write an essay, knowing exactly what you want to write, but then it hits you: you don’t know how to format it! Using the correct format when writing an essay can help your paper look polished and professional while earning you full credit. In this article, we'll teach you the basics of formatting an essay according to three common styles: MLA, APA, and Chicago Style.

Setting Up Your Document

- If you can’t find information on the style guide you should be following, talk to your instructor after class to discuss the assignment or send them a quick email with your questions.

- If your instructor lets you pick the format of your essay, opt for the style that matches your course or degree best: MLA is best for English and humanities; APA is typically for education, psychology, and sciences; Chicago Style is common for business, history, and fine arts.

- Most word processors default to 1 inch (2.5 cm) margins.

- Do not change the font size, style, or color throughout your essay.

- Change the spacing on Google Docs by clicking on Format , and then selecting “Line spacing.”

- Click on Layout in Microsoft Word, and then click the arrow at the bottom left of the “paragraph” section.

- Using the page number function will create consecutive numbering.

- When using Chicago Style, don’t include a page number on your title page. The first page after the title page should be numbered starting at 2. [5] X Research source

- In APA format, a running heading may be required in the left-hand header. This is a maximum of 50 characters that’s the full or abbreviated version of your essay’s title. [6] X Research source

- For APA formatting, place the title in bold at the center of the page 3 to 4 lines down from the top. Insert one double-spaced line under the title and type your name. Under your name, in separate centered lines, type out the name of your school, course, instructor, and assignment due date. [8] X Research source

- For Chicago Style, set your cursor ⅓ of the way down the page, then type your title. In the very center of your page, put your name. Move your cursor ⅔ down the page, then write your course number, followed by your instructor’s name and paper due date on separate, double-spaced lines. [9] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Double-space the heading like the rest of your paper.

Writing the Essay Body

- Use standard capitalization rules for your title.

- Do not underline, italicize, or put quotation marks around your title, unless you include other titles of referred texts.

- A good hook might include a quote, statistic, or rhetorical question.

- For example, you might write, “Every day in the United States, accidents caused by distracted drivers kill 9 people and injure more than 1,000 others.”

- "Action must be taken to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving, including enacting laws against texting while driving, educating the public about the risks, and giving strong punishments to offenders."

- "Although passing and enforcing new laws can be challenging, the best way to reduce accidents caused by distracted driving is to enact a law against texting, educate the public about the new law, and levy strong penalties."

- Use transitions between paragraphs so your paper flows well. For example, say, “In addition to,” “Similarly,” or “On the other hand.” [16] X Research source

- A statement of impact might be, "Every day that distracted driving goes unaddressed, another 9 families must plan a funeral."

- A call to action might read, “Fewer distracted driving accidents are possible, but only if every driver keeps their focus on the road.”

Using References

- In MLA format, citations should include the author’s last name and the page number where you found the information. If the author's name appears in the sentence, use just the page number. [18] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- For APA format, include the author’s last name and the publication year. If the author’s name appears in the sentence, use just the year. [19] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- If you don’t use parenthetical or internal citations, your instructor may accuse you of plagiarizing.

- At the bottom of the page, include the source’s information from your bibliography page next to the footnote number. [20] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Each footnote should be numbered consecutively.

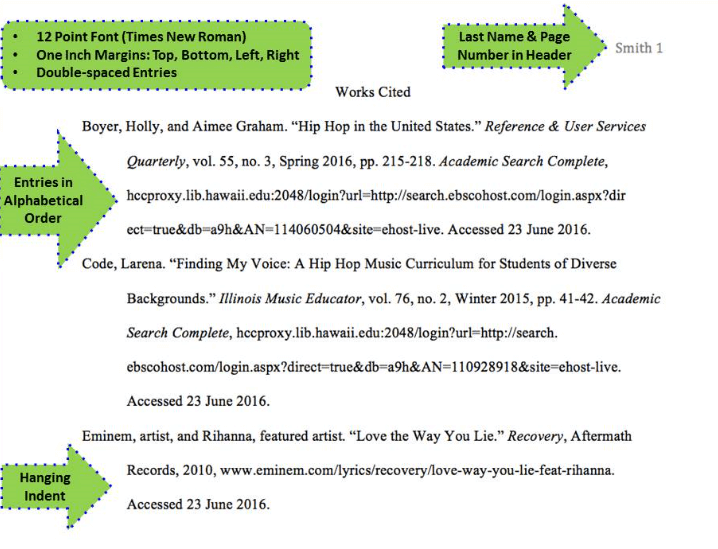

- If you’re using MLA format, this page will be titled “Works Cited.”

- In APA and Chicago Style, title the page “References.”

- If you have more than one work from the same author, list alphabetically following the title name for MLA and by earliest to latest publication year for APA and Chicago Style.

- Double-space the references page like the rest of your paper.

- Use a hanging indent of 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) if your citations are longer than one line. Press Tab to indent any lines after the first. [23] X Research source

- Citations should include (when applicable) the author(s)’s name(s), title of the work, publication date and/or year, and page numbers.

- Sites like Grammarly , EasyBib , and MyBib can help generate citations if you get stuck.

Formatting Resources

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- ↑ https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-englishcomposition1/chapter/text-mla-document-formatting/

- ↑ https://www.une.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/392149/WE_Formatting-your-essay.pdf

- ↑ https://content.nroc.org/DevelopmentalEnglish/unit10/Foundations/formatting-a-college-essay-mla-style.html

- ↑ https://camosun.libguides.com/Chicago-17thEd/titlePage

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/page-header

- ↑ https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/paper-format/title-page

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/chicago_manual_17th_edition/cmos_formatting_and_style_guide/general_format.html

- ↑ https://www.unr.edu/writing-speaking-center/writing-speaking-resources/mla-8-style-format

- ↑ https://cflibguides.lonestar.edu/chicago/paperformat

- ↑ https://www.uvu.edu/writingcenter/docs/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://www.deanza.edu/faculty/cruzmayra/basicessayformat.pdf

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/mla_style/mla_formatting_and_style_guide/mla_in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://monroecollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=589208&p=4073046

- ↑ https://library.menloschool.org/chicago

About This Article

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Maansi Richard

May 8, 2019

Did this article help you?

Jan 7, 2020

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

- Study Documents

- Learning Tools

Writing Guides

- Citation Generator

- Flash Card Generator

- Homework Help

- Essay Examples

- Essay Title Generator

- Essay Topic Generator

- Essay Outline Generator

- Flashcard Generator

- Plagiarism Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Introduction Generator

- Literature Review Generator

- Hypothesis Generator

- Human Editing Service

- Essay Hook Generator

Writing Guides / Complete Guide to Essay Format: MLA, APA, and Chicago Explained

Complete Guide to Essay Format: MLA, APA, and Chicago Explained

Introduction

Content is king, but mastering the mechanics of academic writing is equally important. That’s why formatting your essay matters. Proper formatting allows you to present your essays and term papers clearly, logically, and academically so that it is easy for readers to follow your argument and for instructors to assess your work. Poor formatting, on the other hand, can lead to point deductions, even if the content of your essay is strong.

What is Proper Essay Format?

The format of an essay refers to its basic structure, layout, and appearance on the page. It includes elements such as margins, font size, line spacing, and citation style, among others. Although it may seem daunting at first, mastering the different essay formats is not as difficult as it might appear. The more essays you write, the more familiar you will become with these formats. (Check out this article for more info on how to write an essay ).

Importance of Following Proper Format

Understanding and applying the correct essay format is essential for several reasons. First, it demonstrates your attention to detail and your ability to follow academic conventions. Proper formatting also improves the readability of your essay, allowing your ideas to be presented in a clear and organized manner. Proper formatting is what lets you meet the academic standards expected in your field of study.

Overview of Main Formats

There are several widely recognized essay formats, each commonly used in different academic disciplines. The Modern Language Association ( MLA ) format is often used in the humanities, particularly in literature and language studies. The American Psychological Association ( APA ) format is typically used in the social sciences, such as psychology and education. The Chicago Manual of Style, or Chicago format , is frequently used in history and some social science fields. Each format has its own set of rules for citations, references, and overall layout.

View 120,000+ High Quality Essay Examples

Learn-by-example to improve your academic writing

Standard College Essay Format

There is no universally “right” college essay format, be we do have some commonly accepted guidelines. Professors may have specific preferences, so understanding the standard structure and formatting rules will help you adapt to any requirements.

Basic Components of Any Essay

- Title Page : This usually includes the title of your essay, your name, the course name, the instructor’s name, and the date of submission. The title should be centered and written in a standard font, without italics or underlining.

- Introduction : The introduction is the opening paragraph of your essay, where you present the topic and your thesis statement . It should contain a hook, a brief overview of the main points that will be discussed in the body of the essay, and your main point.

- Body : The body of the essay is where you develop your arguments or analysis in detail. Each paragraph of the body should focus on a specific point or piece of evidence that supports your thesis.

- Conclusion : The conclusion is the final paragraph of your essay, where you summarize the main points and restate your thesis in light of the evidence presented. It should contain no new info, but should leave lasting impression on the reader so as to reinforce the significance of your essay.

- Bibliography : Also known as the Works Cited or References page, the bibliography lists all the sources you cited in your essay. The format of the bibliography varies depending on the citation style (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc.), but it typically includes the author’s name, title of the work, publication information, and date.

General Formatting Rules

- Fonts : Standard college essays typically use a uniform font for consistency and readability. Times New Roman is the most widely accepted font, though Arial is sometimes permitted. The font size is usually set to 12 points. Font should be consistent across the entire document.

- Line Spacing : Most college essays require double spacing. Occasionally, you may be asked to use single spacing or 1.5 spacing, depending on the instructor’s preference or the specific assignment guidelines.

- Margins : The standard margin size for college essays is one inch on all sides (top, bottom, left, and right). This margin size is typically the default setting in Word.

- Page Numbers : Including page numbers in your essay is generally expected, especially for longer assignments. Page numbers are usually placed in the upper right corner of each page, sometimes accompanied by your last name or the title of the essay.

- Title Page : Short essays often do not require a title page, but for longer essays or research papers, a title page will probably be mandatory. If required, the title page should follow the specific format outlined by your instructor (APA, MLA, etc.), typically including the title of the essay, your name, course details, and submission date.

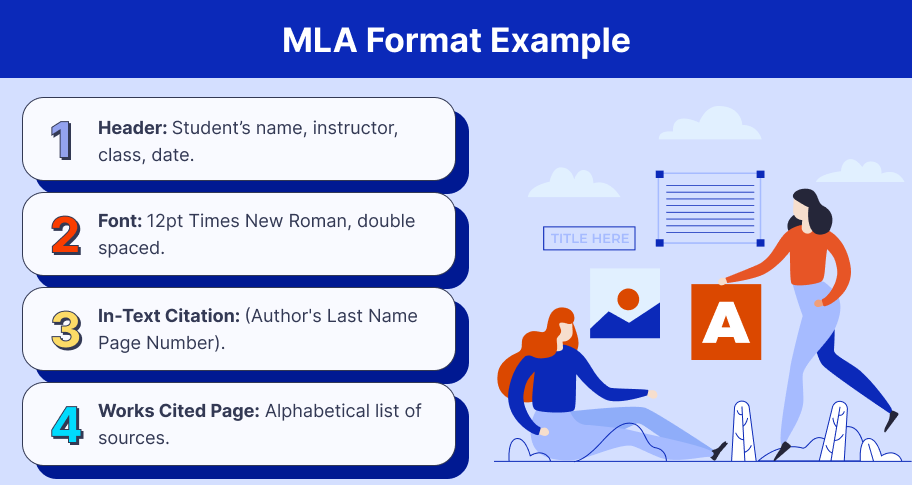

MLA Essay Format

Mla structure and layout.

MLA format is known for its simplicity. The following are the basic components of an essay written in MLA format:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman) : Times New Roman in 12-point font is the standard typeface used in MLA format.

- First Line Indent : Each paragraph in an MLA-formatted essay begins with an indentation of the first line, typically set at half an inch from the left margin. This indentation visually separates paragraphs, which makes the essay easy to read.

- Double-Spacing : The entire essay should be double-spaced, including the text, block quotes, and the Works Cited page. Double spacing should be consistent throughout. It is especially helpful as it allows space for instructors to make annotations.

- 1-Inch Margins : MLA format requires uniform 1-inch margins on all sides of the page (top, bottom, left, and right), which keeps the page balanced in appearance.

- Header : Unlike APA format, MLA does not usually require a title page. Instead, your name, your professor’s name, the course name, and the date should be listed in the upper left-hand corner of the first page. Below this information, the title of the essay should be centered and written in standard title case (capitalizing the first and main words of the title). A header with your last name and page number should appear in the upper right corner of each page, beginning with the first page.

MLA In-Text Citations and Works Cited

MLA format has specific guidelines for citing sources both within the text and in the Works Cited page. These citations are crucial for giving credit to the original authors and for allowing readers to trace the sources of your information.

- In-Text Citations : In MLA format, in-text citations are brief and are usually placed at the end of the sentence before the period. They include the author’s last name and the page number where the information was found, all within parentheses. For example: (Smith 123). If the author’s name is mentioned in the sentence, only the page number is required in the citation: (123). Even when paraphrasing or summarizing, the page number must be included, which can be a challenge but is essential to meet MLA standards.

- Works Cited Page : The Works Cited page appears at the end of the essay and lists all the sources referenced in your paper. Each entry should be formatted with a hanging indent, where the first line of the citation is flush with the left margin, and subsequent lines are indented. Entries are listed alphabetically by the author’s last name or by the title if no author is provided. The general format for a book citation in MLA is: Author’s Last Name, First Name. Title of Book . Publisher, Year of Publication.

MLA Common Mistakes to Avoid

While MLA format is straightforward, there are common mistakes that students often make:

- Incorrect In-Text Citations : Failing to include the page number, using the wrong format for the author’s name, or placing the period outside the parentheses are frequent errors. Always double-check your in-text citations for accuracy.

- Improper Works Cited Formatting : Not following the correct order, incorrect use of italics or quotation marks, and missing publication details are common pitfalls. Ensure each entry adheres to MLA guidelines.

- Missing or Incorrect Header : Forgetting to include the header with your last name and page number on each page can lead to a lower grade. Also, ensure that the header is properly aligned with the right margin.

Example of MLA Format

Here’s a simplified example of how the first page of an MLA-formatted essay might look:

First Page of an MLA Paper :

APA Essay Format

Apa structure and layout.

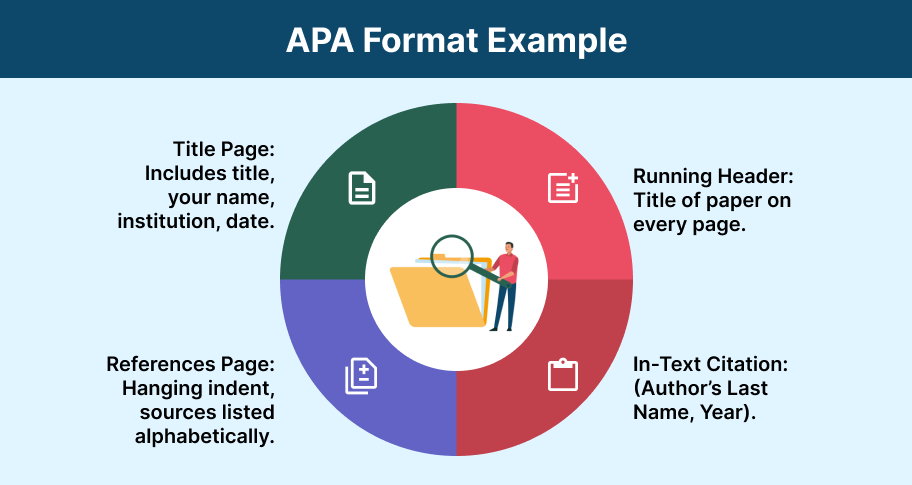

APA format follows a set structure that includes a title page, abstract, body, and references.

- Title Page : The title page in APA format is crucial as it sets the tone for your paper. It includes the title of your essay, your name, and your institutional affiliation, all centered on the page. The title should be concise and informative, reflecting the content of your paper. Below the title, your name appears, followed by your institution (e.g., university name). Some instructors may ask for additional information like the course title, instructor’s name, and the date.

- Abstract : The abstract is a brief summary of your paper, usually between 150-250 words. It gives a summary of your research, including the research question, methods, results, and conclusions. The abstract appears on its own page, right after the title page, and is typically a single paragraph without indentation. Abstracts are used in longer research papers and dissertations to give readers a quick snapshot of the study’s content and findings.

- Body : The body of an APA paper is where you present your argument or findings. It starts on a new page after the abstract and is divided into sections such as the introduction, method, results, discussion, and conclusion, depending on the type of paper you are writing. Each section may include subheadings to improve organization and readability.

- References : The reference page, which comes at the end of your paper, lists all the sources cited in the text. This page follows specific APA formatting rules, including the use of a hanging indent and alphabetical order by the authors’ last names. The reference entries must include detailed information about each source, such as the author’s name, publication year, title of the work, and source.

APA In-Text Citations and References

APA style uses the author-date citation method, which includes the author’s last name and the publication year in the text. This method allows readers to locate the full citation in the reference list easily.

- In-Text Citations : In-text citations in APA format are concise. For example, if you’re citing a book by John Doe published in 2020, the citation would appear as (Marve, 2024). If you directly quote a source, you must also include the page number: (Smith & Wesson, 2023, p. 15). These citations are usually placed at the end of a sentence before the period.

- References : Every in-text citation must correspond to an entry in the reference list. The reference list provides full details about the source, formatted in a specific way. For a book, the format is: Author’s Last Name, First Initial(s). (Year). Title of the book . Publisher.

APA Headings and Subheadings

Headings and subheadings are essential in APA format as they help organize the content and guide readers through the paper. APA uses a specific hierarchy of headings:

- Level 1 Heading : Centered, Bold, Title Case (e.g., Introduction)

- Level 2 Heading : Flush Left, Bold, Title Case (e.g., Review of Literature)

- Level 3 Heading : Indented, Bold, Sentence case, ending with a period. (e.g., Methods)

Subheadings break down sections into more detailed parts, making your essay easier to follow.

Example of APA Format

Chicago Essay Format

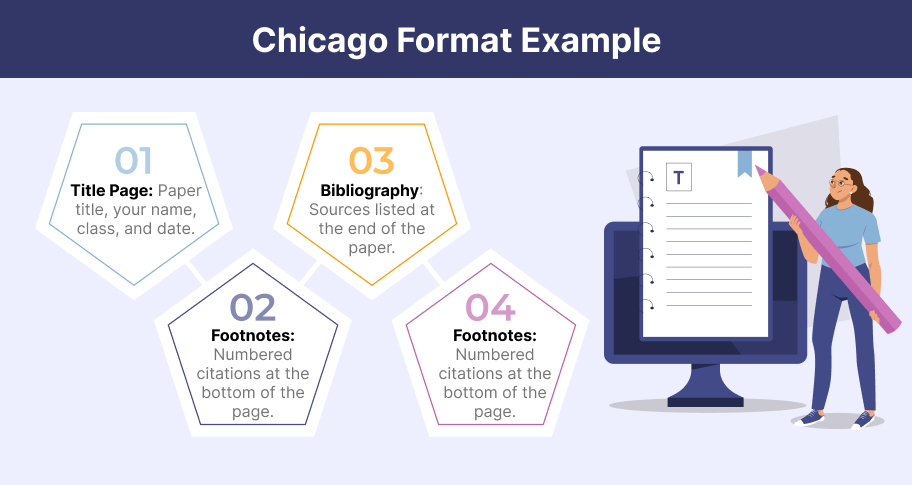

Overview of chicago style.

Chicago style follows a standard set of formatting guidelines, which include:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman) : Chicago style typically uses Times New Roman in 12-point font, which is considered a classic and highly readable typeface.

- First Line Indent : Each paragraph should begin with a half-inch indent, creating a clear separation between sections of text.

- Double-Spacing : The entire document, including block quotes, notes, and bibliography, should be double-spaced, providing ample room for comments or corrections.

- 1-Inch Margins : Chicago style requires 1-inch margins on all sides of the page, which is standard for most academic papers.

Chicago style is known for its flexibility, especially in the way it handles citations. Unlike MLA or APA formats, which rely on in-text parenthetical citations, Chicago style allows for the use of either footnotes or endnotes, which are a less obtrusive way to cite sources.

Chicago Footnotes vs. Endnotes

- Footnotes : Footnotes appear at the bottom of the page on which the reference is made. They are numbered consecutively throughout the essay. Footnotes are preferred when you want the reader to have immediate access to the source or explanation while reading the text. For example, after quoting a source, a small superscript number is placed at the end of the sentence, corresponding to a footnote at the bottom of the page, where full citation details are provided.

- Endnotes : Endnotes, like footnotes, are numbered consecutively but are placed at the end of the essay, just before the bibliography. Endnotes are often used in longer works where multiple citations might overwhelm the page layout. While they serve the same purpose as footnotes, they require the reader to flip to the end of the document to see the citation, which some writers prefer to keep the main text uncluttered.

Both footnotes and endnotes in Chicago style include detailed citation information, such as the author’s name, title of the work, publication details, and page numbers. The choice between footnotes and endnotes often depends on the nature of the paper and the instructor’s preference.

Chicago Bibliography Format

The bibliography in Chicago style lists all sources referenced in the paper. The bibliography page appears at the end of the essay and should follow these guidelines:

- Alphabetical Order : Entries in the bibliography are listed alphabetically by the author’s last name. If no author is provided, the title of the work is used.

- Hanging Indent : Each entry begins flush with the left margin, and subsequent lines are indented by half an inch. This format is known as a hanging indent.

- Detailed Citations : Each entry should include the author’s name, the title of the work (italicized), the place of publication, the publisher, and the year of publication. For example: Smith, John. The History of Modern Europe . New York: Random House, 2020.

Example of Chicago Format

Here’s an example of how a Chicago-style essay might look:

Title Page Example :

Key Differences Between MLA, APA, and Chicago

Citation styles.

- MLA (Modern Language Association) : MLA style is typically used in the humanities, particularly in literature, philosophy, and the arts. Citations are made using brief parenthetical references within the text, including the author’s last name and page number (e.g., Mason 413). The full citation details are provided in a Works Cited page at the end of the document.

- APA (American Psychological Association) : APA format is prevalent in the social sciences, including psychology, sociology, and education. It uses the author-date method for in-text citations, where the author’s last name and the year of publication are included (e.g., Como, 2020). A References page at the end lists all sources in full detail.

- Chicago Style : Chicago style, often used in history, political science, and the arts, offers two citation methods: the Notes and Bibliography system, which uses footnotes or endnotes along with a bibliography, and the Author-Date system, similar to APA but less commonly used. Footnotes or endnotes provide detailed source information at the bottom of the page or at the end of the paper, making this style flexible for detailed commentary.

Paper Structure

The structure of a paper also varies among these formats:

- MLA : MLA format is straightforward, typically consisting of a title page (optional), an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion. It does not require a separate title page; instead, the student’s name, instructor’s name, course, and date are placed at the top of the first page.

- APA : APA format is more structured and includes a title page, abstract, main body, and references. The title page presents the title, author’s name, and institutional affiliation, while the abstract provides a brief summary of the paper. APA also often uses headings and subheadings to organize content clearly.

- Chicago : Chicago format is flexible and can vary based on the type of paper. A typical Chicago-style paper includes a title page, the main body of text, and a bibliography. When using the Notes and Bibliography system, Chicago style also incorporates footnotes or endnotes, which can make the structure appear more complex.

Where and When to Use Each Format

Each format is suited to specific academic disciplines:

- MLA : Best used in humanities subjects, especially in writing-intensive courses where the focus is on literary analysis, criticism, or cultural studies.

- APA : Ideal for the social sciences, where research often involves data analysis, experiments, and empirical studies. APA’s structured format helps present research findings clearly.

- Chicago : Often required in history, art history, and some social sciences. It is particularly useful when extensive citation or commentary is needed, thanks to its footnote and endnote options.

Special Essay Formats

When you’re applying for a scholarship, submitting a college application, or crafting a research or persuasive essay, know that each format has unique elements that guide how you should present your work.

Scholarship Essay Format

Scholarship essays are critical for students aiming to secure financial aid for their education. Unlike standard academic essays, a scholarship essay is deeply personal and written in the first person. It focuses on your achievements, goals, and reasons for deserving the scholarship. Here are some key aspects of the scholarship essay format:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman or Arial) : This is the standard for readability.

- First Line Indent : Each paragraph should begin with an indentation, creating a clear structure.

- Double-Spacing : Double-spacing improves readability and allows room for comments.

- 1-Inch Margins : Standard margins provide a clean, professional look.

Unlike academic essays that are typically written in the third person, scholarship essays are personal narratives. The essay should show your determination, goals, and the unique qualities that make you a worthy candidate. Discuss your academic achievements, community involvement, and future aspirations, while avoiding generic statements. Tailor each essay to the specific scholarship, addressing the organization’s values and how they align with your goals.

College Application Essay Format

College application essays are crucial in the admissions process. They offer a glimpse into your personality, values, and potential contributions to the college community. These essays are also written in the first person and vary in length, from short responses to longer personal statements. Key formatting elements include:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman or Arial) : Consistency in font choice helps maintain a formal tone.

- First Line Indent : Indenting paragraphs helps organize your thoughts.

- Double-Spacing : This spacing standard enhances readability and presentation.

- 1-Inch Margins : Uniform margins contribute to a polished appearance.

A strong college application essay often begins with a thoughtful introduction, perhaps a personal anecdote or a significant experience that shaped your character. The body of the essay should go into your interests, goals, and why you are drawn to the specific college or program. Be authentic and reflective. This essay is your chance to stand out among many applicants, so it’s important to convey your own unique story.

Research Essays (Extended Essays, IB Essays)

Research essays, such as those required for International Baccalaureate (IB) programs or extended essays, are more formal and structured than personal essays. These essays require rigorous research and a thorough analysis of the topic. The format for research essays generally includes:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman or Arial) : A professional and readable font choice.

- First Line Indent : Each paragraph should be clearly indented.

- Double-Spacing : Allows for clear presentation and space for feedback.

- 1-Inch Margins : Standard for most academic papers.

- Title Page and Abstract : Depending on the requirements, these elements may be necessary, particularly in extended essays or formal research papers.

Research essays are structured around a thesis statement, with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. The body should be divided into sections, each addressing different aspects of the research question, supported by evidence from credible sources. Use proper citation to avoid plagiarism charges and to give credit to original ideas.

Reflective and Persuasive Essays

Reflective and persuasive essays require different approaches but share some formatting similarities with standard essays.

Reflective Essay : Reflective essays explore personal experiences and the insights gained from them. The format may include:

- 12-Point Font (Times New Roman or Arial) .

- First Line Indent .

- Double-Spacing .

- 1-Inch Margins .

In a reflective essay, you may be asked to consider a personal experience or react to a text, event, or artwork. The essay should include a description of the experience or object of reflection, followed by an analysis of its impact on you. The tone can be informal, but the structure should remain coherent and well-organized.

Persuasive Essay : Persuasive essays aim to convince the reader of a particular point of view. They follow a more traditional academic structure:

Persuasive essays require a strong thesis statement, clear arguments supported by evidence, and a conclusion that reinforces your position. Use rhetorical strategies like ethos, pathos, and logos to strengthen your argument and persuade the reader effectively. Acknowledge opposing views and refute them to build a more compelling case.

Additional Formatting Tips

Creating an outline.

An outline helps you organize your thoughts and structure your essay logically. It serves as a roadmap, guiding you through each section of your paper and ensuring that your arguments flow coherently. An effective outline typically includes:

- Introduction : Start with your thesis statement, followed by a brief overview of the main points you will discuss.

- Body Paragraphs : List the key points or arguments you plan to make, organized into sections. For each section, include supporting evidence or examples.

- Conclusion : Summarize your main points and restate your thesis in a new light, reflecting the arguments made in the body.

Using bullet points or numbering in your outline can help you maintain a clear hierarchy of ideas. While the outline itself is not part of the final essay, creating one can save time during the writing process and improve the overall structure of your paper.

Formatting Headings and Subheadings

Headings and subheadings are essential for breaking up the text and guiding readers through your essay. They provide a clear structure, making it easier for readers to follow your argument. Different formatting styles have specific rules for headings and subheadings:

- MLA : Generally does not require headings, but when used, they should be formatted consistently without a boldface or italics.

- APA : APA uses a five-level heading system. Level 1 is centered and bold, Level 2 is flush left and bold, and so on, down to Level 5, which is indented, bold, and italicized.

- Chicago : Offers flexibility, but generally, headings are bolded or italicized, and subheadings are formatted similarly but in a smaller font size or with less emphasis.

Using clear and consistent formatting for your headings and subheadings helps organize the content and makes your essay more reader-friendly.

Formatting Tables, Charts, and Appendices

Including tables, charts, and appendices in your essay can be an effective way to present data, summarize information, or provide additional context without overcrowding the main text. Proper formatting of these elements is crucial to maintain the professionalism of your document.

- Labeling : Each table and chart should be labeled with a number (e.g., Table 1, Figure 2) and a descriptive title.

- Placement : Tables and charts can be placed within the text close to where they are referenced or included at the end of the document in an appendix.

- Formatting : Ensure that tables are clear, with consistent font and spacing, and that charts are accurately labeled with legends if needed.

- Purpose : Appendices are used to include supplementary material that is relevant but not essential to the main text, such as raw data, questionnaires, or detailed explanations.

- Labeling : Appendices should be labeled (e.g., Appendix A, Appendix B) and referenced in the main text.

- Content : Each appendix should start on a new page, with the title clearly labeled at the top.

Formatting is a big aspect of academic writing that goes beyond mere aesthetics. Proper formatting gives clarity, readability, and professionalism. Whether you’re using MLA, APA, Chicago, or another style, adhering to the specific guidelines of each format will show your attention to detail and your commitment to academic standards.

A well-formatted essay not only makes your work more accessible to readers but it also improves the credibility of your arguments. Be careful about organizing your content with appropriate headings, citations, and supplementary materials like tables or appendices, so that you can turn in a well-structured and persuasive piece of writing.

Final tips: always double-check the specific requirements of your assignment and seek clarification from your instructor if needed. Utilize tools like outlines to plan your essay structure, and pay attention to the nuances of each style, such as citation formats and the use of footnotes or endnotes. Master these elements, and you’ll be able to effectively communicate your ideas and enjoy academic success.

Take the first step to becoming a better academic writer.

Writing tools.

- How to write a research proposal 2021 guide

- Guide to citing in MLA

- Guide to citing in APA format

- Chicago style citation guide

- Harvard referencing and citing guide

- How to complete an informative essay outline

How to Choose the Best Essay Topics

AI Text Detection Services

Unlock Your Writing Potential with Our AI Essay Writing Assistant

The Negative Impacts of Artificial Intelligence on Tactile Learning

Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

How to Format A College Essay: 15 Expert Tips

College Essays

When you're applying to college, even small decisions can feel high-stakes. This is especially true for the college essay, which often feels like the most personal part of the application. You may agonize over your college application essay format: the font, the margins, even the file format. Or maybe you're agonizing over how to organize your thoughts overall. Should you use a narrative structure? Five paragraphs?

In this comprehensive guide, we'll go over the ins and outs of how to format a college essay on both the micro and macro levels. We'll discuss minor formatting issues like headings and fonts, then discuss broad formatting concerns like whether or not to use a five-paragraph essay, and if you should use a college essay template.

How to Format a College Essay: Font, Margins, Etc.

Some of your formatting concerns will depend on whether you will be cutting and pasting your essay into a text box on an online application form or attaching a formatted document. If you aren't sure which you'll need to do, check the application instructions. Note that the Common Application does currently require you to copy and paste your essay into a text box.

Most schools also allow you to send in a paper application, which theoretically gives you increased control over your essay formatting. However, I generally don't advise sending in a paper application (unless you have no other option) for a couple of reasons:

Most schools state that they prefer to receive online applications. While it typically won't affect your chances of admission, it is wise to comply with institutional preferences in the college application process where possible. It tends to make the whole process go much more smoothly.

Paper applications can get lost in the mail. Certainly there can also be problems with online applications, but you'll be aware of the problem much sooner than if your paper application gets diverted somehow and then mailed back to you. By contrast, online applications let you be confident that your materials were received.

Regardless of how you will end up submitting your essay, you should draft it in a word processor. This will help you keep track of word count, let you use spell check, and so on.

Next, I'll go over some of the concerns you might have about the correct college essay application format, whether you're copying and pasting into a text box or attaching a document, plus a few tips that apply either way.

Formatting Guidelines That Apply No Matter How You End Up Submitting the Essay:

Unless it's specifically requested, you don't need a title. It will just eat into your word count.

Avoid cutesy, overly colloquial formatting choices like ALL CAPS or ~unnecessary symbols~ or, heaven forbid, emoji and #hashtags. Your college essay should be professional, and anything too cutesy or casual will come off as immature.

Mmm, delicious essay...I mean sandwich.

Why College Essay Templates Are a Bad Idea

You might see college essay templates online that offer guidelines on how to structure your essay and what to say in each paragraph. I strongly advise against using a template. It will make your essay sound canned and bland—two of the worst things a college essay can be. It's much better to think about what you want to say, and then talk through how to best structure it with someone else and/or make your own practice outlines before you sit down to write.

You can also find tons of successful sample essays online. Looking at these to get an idea of different styles and topics is fine, but again, I don't advise closely patterning your essay after a sample essay. You will do the best if your essay really reflects your own original voice and the experiences that are most meaningful to you.

College Application Essay Format: Key Takeaways

There are two levels of formatting you might be worried about: the micro (fonts, headings, margins, etc) and the macro (the overall structure of your essay).

Tips for the micro level of your college application essay format:

- Always draft your essay in a word processing software, even if you'll be copy-and-pasting it over into a text box.

- If you are copy-and-pasting it into a text box, make sure your formatting transfers properly, your paragraphs are clearly delineated, and your essay isn't cut off.

- If you are attaching a document, make sure your font is easily readable, your margins are standard 1-inch, your essay is 1.5 or double-spaced, and your file format is compatible with the application specs.

- There's no need for a title unless otherwise specified—it will just eat into your word count.

Tips for the macro level of your college application essay format :

- There is no super-secret college essay format that will guarantee success.

- In terms of structure, it's most important that you have an introduction that makes it clear where you're going and a conclusion that wraps up with a main point. For the middle of your essay, you have lots of freedom, just so long as it flows logically!

- I advise against using an essay template, as it will make your essay sound stilted and unoriginal.

Plus, if you use a college essay template, how will you get rid of these medieval weirdos?

What's Next?

Still feeling lost? Check out our total guide to the personal statement , or see our step-by-step guide to writing the perfect essay .

If you're not sure where to start, consider these tips for attention-grabbing first sentences to college essays!

And be sure to avoid these 10 college essay mistakes .

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Ellen has extensive education mentorship experience and is deeply committed to helping students succeed in all areas of life. She received a BA from Harvard in Folklore and Mythology and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Columbia University.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

How to Structure & Layout Your Essay

MSt, Women's, Gender & Sexuality Studies (University of Oxford)

Share this article

Key Elements of Essay Structure

A clear, organized structure can make all the difference for an essay, helping your argument become more understandable and persuasive. The overall structure of your essay should look like this:

- Introduction: Introduce your topic and state your argument.

- Body : Present each of the main points that prove your argument, backed up with evidence.

- Conclusion: Reiterate your argument and conclude your paper.

The Body of the essay is the bulk of your paper; in a five page essay, you might dedicate one or two paragraphs each to your introduction and conclusion, and the rest of the paper to proving your points with evidence.

Let’s look at these sections more closely so we can learn how to structure each of them.

Introduction

Your introduction sets up your reader’s expectations for the essay. You introduce your topic, your argument, and your voice as a writer. In general, follow this structure for your introduction:

- Hook the reader: Start with a sentence or two to capture the reader’s attention. A good hook is catchy and relevant to your argument.

- Orient the reader to the topic, context, and key terms: Introduce your reader to the topic at hand and offer any background or contextual information they might need to understand your essay. Define key terms or technical words you’ll be using throughout your essay.

- Ask your research question: Your essay should be a response to a puzzle/problem/contradiction that you can phrase as a question. State it so your reader knows what you’re trying to figure out.

- State your thesis: Finish your introduction by presenting what you intend to argue.

More in-depth information about all of these elements can be found in our guide to writing an effective introduction .

Your introduction can also forecast the structure of your essay . Particularly when dealing with long papers, theses with multiple logical steps, and essays with distinct sections (historical context, literature review, etc.), outlining the path of your paper in the introduction can help your reader follow your argument and anticipate what is to follow.

The body of the essay is where most issues with structure tend to arise. How much evidence do you need? How often do you include scholars’ perspectives versus your own? How many points are you making — and what are they really saying ? As a writer, you have a lot to balance. But if you follow these tips and tricks, your body paragraphs will be clear and organized, working together to build your argument.

One paragraph = one main point .

You should be able to summarize each body paragraph with one main point that ties into your larger argument. This point is typically stated in a topic sentence at the start of the paragraph. If you look only at the topic sentences of your body paragraphs, you should have an outline of your argument.

Read over a body paragraph. Can you summarize what you argue in that paragraph in one bullet point? If not, split up the paragraph so you can.

Paragraphs should build , not repeat .

When first learning how to write an essay, you might have written body paragraphs that each essentially proved the same point through different examples. For example, in an essay arguing that Shylock is actually the hero of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice , each paragraph may have been dedicated to an instance when Shylock was presented sympathetically. If you’re making the same point in each paragraph, just with different examples, your essay can quickly get boring and your thesis appears too obvious (even if it’s not).

Instead, think of your essay as building on itself, each paragraph making a slightly different point that all work together to prove your overarching argument. A lawyer wouldn’t just introduce evidence that shows motive in a trial; they must introduce evidence showing means, motive, and opportunity — and show how they all connect — in order to prove a case.

To give an overly simplistic edit to the Shylock essay, you might argue that Shylock is the hero of The Merchant of Venice because he exhibits all the qualities of a tragic hero, delivers the most rhetorically complex speeches, and is the titular character. This version of the essay will make a different point in each paragraph with different examples, but they all bolster the overall argument.

An even more advanced essay would consider how the points build on each other and be structured so each paragraph is necessary for the next, growing the argument throughout the paper.

Although in the Shylock example, it seems like there are three main points which support the overall assertion (that Shylock is a hero), do not feel like you need to make your argument with only three main points. The “five paragraph essay” (one paragraph introduction, three body paragraphs, one paragraph conclusion) can be helpful when learning how to build an argument, but there is no need to hold yourself to only three points! Even the example above might require more than three body paragraphs: when discussing how Shylock exhibits the qualities of a tragic hero, the writer might need a few paragraphs to introduce what those qualities are and how Shylock exhibits each of them.

Balance evidence and analysis.

In your body paragraphs, it’s important to present evidence supporting your thesis and analyze that evidence for your reader, tying the pieces together into a cohesive argument.

Strategically engage with other scholars.

The hamburger method focuses on analyzing primary sources , the raw materials you’re working with (a data set, a poem, an artwork). But as you advance as a writer, you’ll also be working with secondary sources , what other scholars have written. It can be tricky to figure out how much you should rely on the voices of other scholars versus your own to make your argument. You don’t want to be drowned out by a sea of other voices.

When dealing with secondary source material, always ask yourself: what is this doing for my argument? Are you bringing up a scholar’s perspective to help you make a larger point? Or are you setting them up to be refuted by your new interpretation of the evidence? You can agree with scholars throughout your paper, but your larger argument should say something slightly new.

Secondary source material can work in your essay as cheese and toppings on the burger, helping you analyze the primary evidence you’ve introduced (though don’t get too carried away with toppings that you lose the burger itself!). You can also treat secondary source material as the meat of the burger if you’re trying to work through what another scholar said or want to point out a gap in the literature.

Whenever you introduce material outside of your own voice, from primary or secondary sources, be sure to explain to your reader how it connects to your argument.

Signal your structure to the reader with signposts and transitions.

A good structure makes your argument as clear as possible to the reader. It helps to guide the reader through your essay with words that signal where they are and transitions that show how points fit together. Here are some words and phrases you might use:

- based on this evidence…

- looking at this passage…

- it seems like… but upon further investigation….

- before addressing…let’s understand…

- with an understanding of…this essay now turns to…

TOOL: The X-Ray, or the Reverse Outline

An x-ray or reverse outline is a helpful tool for diagnosing structural problems. Once you’ve written a rough draft, use this tool to see where your structure might need to be improved and whether the analysis in your body paragraphs is reflecting your thesis and main points.

Read your essay. Next to each paragraph, try to summarize the main point of that paragraph with a heading, bullet point, or short sentence.

Ask yourself:

- Are there multiple points in this paragraph? If so, it should probably be two paragraphs, not one.

- Is the point of this paragraph implied rather than stated? Do I have a topic sentence that makes the point of this paragraph clear to my reader and a concluding sentence that reminds the reader what the main takeaway is?