Theoretical sampling

Theoretical sampling can be defined as “the process of data collection for generating theory whereby the analyst jointly collects, codes and analyses his data and decides what data to collect next and where to find them in order to develop his theory as it emerges” [1] . In simple terms, theoretical sampling can be defined as the process of collecting, coding and analyzing data in a simultaneous manner in order to generate a theory. This sampling method is closely associated with grounded theory methodology.

It is important to make a clear distinction between theoretical sampling and purposive sampling . Although it is a variation of the purposive sampling, unlike a standard purposive sampling , theoretical sampling attempts to discover categories and their elements in order to detect and explain interrelationships between them.

Theoretical sampling is associated with grounded theory approach based on analytic induction. Theoretical sampling is different from many other sampling methods in a way that rather than being representative of population or testing hypotheses, theoretical sampling is aimed at generating and developing theoretical data.

Theoretical sampling may not be necessary for bachelor level or even master’s level dissertations since it is the most complicated and time consuming sampling method. However, theoretical sampling is well suited to be applied for PhD-level studies.

Application of Theoretical Sampling: an Example

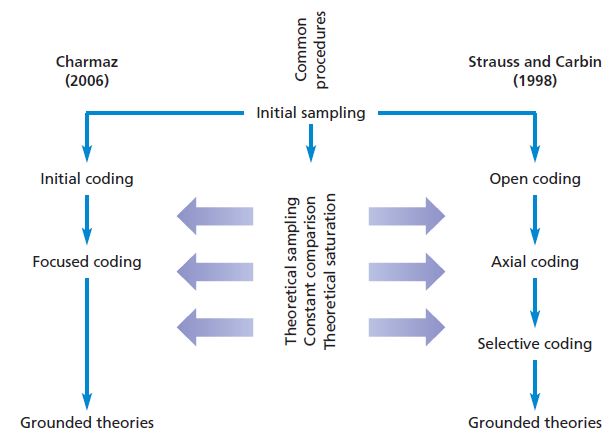

Theoretical sampling cannot be planned in a detailed manner before primary data collection process. As it is illustrated in figure below, theoretical sampling is systematically applied throughout the research process up to the generation of the grounded theory.

Theoretical sampling and generation of grounded theory [2]

Let’s illustrate the application of this sampling method by using a basic example. Imagine your dissertation topic is the following:

The impact of the Brexit on emotional wellbeing of consumers in Birmingham

The application of semi-structured interviews and theoretical sampling to complete this study will involve the following four steps:

Step 1: Make initial decisions are made regarding specific individuals or groups of people who have knowledge about the research area.

Semi-structured interviews need to be conducted with about heads of 15 households in order to assess the impact of the Brexit on them on emotional level.

Step 2: Analyse the initial data until theoretical ideas start to emerge and particular concepts arise.

Analysis of interview results may reveal that interviewees enjoy a sense of independence as a result of Brexit, however, they are concerned about their future at the same time.

Step 3: Choose further participants, events or situations on the basis of theoretical ideas and concepts revealed in the previous stage.

In our case more participants need to be selected in order to indentify the exact nature of Brexit-related concerns via conducting semi-structured interviews.

Step 4: Continue with steps 2 and 3 above until theoretical saturation is reached. Theoretical saturation “signals the point in grounded theory at which theorizing the events under investigation is considered to have come to a sufficiently comprehensive end”. [3]

Results of additional numerous interviews may reveal that weakening pound, the UK’s currency and the loss of special privileges in trading with EU-member states are the main source of concern for the sample group members with direct implications on their emotional wellbeing. This finding may re-occur time and time again with additional interviews indicating that theoretical saturation has been reached.

It is important to stress that unlike other sampling methods, theoretical sampling cannot be pre-planned and from the outset, but occurs at a later stage of the research process.

Advantages of Theoretical Sampling

- The possibility to strengthen the rigor of the study if the study attempts to generate a theory in the research area.

- The application of theoretical sampling method can provide a certain structure to data collection and data analysis processes, thus addressing one of the main disadvantages of qualitative methods that relate to lack of structure.

- This type of sampling usually integrates both, inductive and deductive characteristics, thus increasing comprehensiveness of studies.

Disadvantages of Theoretical Sampling

- Because it is a highly systematic process, application of theoretical sampling method may require more resources such as time and money compared to many other sampling methods.

- There are no clear processes or guidance related to the application of theoretical sampling in practice

- Overall, theoretical sampling is the most complicated than other sampling methods

My e-book, The Ultimate Guide to Writing a Dissertation in Business Studies: a step by step approach contains a detailed, yet simple explanation of sampling methods . The e-book explains all stages of the research process starting from the selection of the research area to writing personal reflection. Important elements of dissertations such as research philosophy , research approach , research design , methods of data collection and data analysis are explained in this e-book in simple words.

John Dudovskiy

[1] Glaser, B.G. & Strauss, A.L. (2012) “The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research” Aldine Transaction

[2] Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2012) “Research Methods for Business Students” 6 th edition, Pearson Education Limited

[3] Given, L.M. (20080) “The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods” SAGE

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Access

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Extended Case Method

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Theoretical Sampling

- Multi-Sited Ethnography

- Triangulation

- Snowball Sampling

- Comparative Case Studies

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Agent Based Models

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Qualitative Longitudinal Research

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Gatekeepers in Ethnography

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Case Study

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Gatekeepers in Qualitative Research

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Central Limit Theorem

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Respondent-Driven Sampling

- Randomization

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Kish, Leslie

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Nonprobability Sampling

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Experience Sampling

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Survey Weights

- FOUNDATION ENTRY Model-Based Inferences

Discover method in the Methods Map

Theoretical sampling.

- By: Rosaline S. Barbour | Edited by: Paul Atkinson, Sara Delamont, Alexandru Cernat, Joseph W. Sakshaug & Richard A.Williams

- Publisher: SAGE Publications Ltd

- Publication year: 2022

- Online pub date: June 21, 2022

- Methods: Theoretical sampling , Sampling , Purposive sampling

- Length: 10k+ Words

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781526421036785176

- Online ISBN: 9781529746099 More information Less information

- What's Next

Theoretical sampling involves anticipation of the likely differences in responses of research participants. Such tentative hypotheses are then utilized by the researcher in order to select respondents, groups, or research settings/sites with a view to affording a basis for comparison, once the data have been generated. Although theoretical sampling choices are often made at the outset of a study, it is also possible to retrospectively carry out further comparisons. Analysis involves interrogating initial hypotheses, and other potentially important criteria or attributes may well be identified as data generation and analysis unfold. Reflecting the iterative nature of qualitative research, this entry stresses that sampling, data elicitation, and preliminary analysis proceed hand in hand. This means that it is not possible to give a definitive set of guidelines with regard to how to carry out theoretical sampling. Rather, this entry seeks to provide an overview of the variants involved in theoretical sampling practice, with differing levels of sophistication in terms of hypotheses that inform researchers’ decision-making. The use of structured approaches (involving sampling grids and screening questionnaires) is examined, as is the often overlooked theorizing that informs ethnographies or case study research. Finally, the role of spontaneity and the potential for more creative approaches is explored.

Introduction

The concept of theoretical sampling lies at the very heart of the qualitative research endeavour. However, due, perhaps, to the previous ascendancy of quantitative methods—and the somewhat different implications of sampling for quantitative enquiry—sampling is often considered in terms of a procedure that occurs only at the outset of a study. If, instead, it is viewed as an iterative process, potentially happening throughout a research project, then many other possibilities open up. Drawing on examples from a range of research topics and disciplinary areas, this entry explores the variants of theoretical sampling; their role at different stages of the research project; and their enormous—although frequently overlooked—potential.

At its simplest, theoretical sampling refers to researchers’ envisaging as to which characteristics or circumstances are likely to influence perceptions, understandings, and behaviour and using this to inform their choice of settings, case studies, respondents, or participants (depending on the nature of their enquiry). Selecting on the basis of gender, age, or social class, for example, is also sometimes referred to as purposive sampling —the purpose being to afford potential for comparison. Even studies that rely on convenience samples (relying on footfall; e.g., simply selecting those attending a specific clinic) can benefit from a retrospective “purposive glance,” which may, in turn, suggest further criteria or avenues for sampling.

Central to the notion of purposive or theoretical sampling is the idea of generating and testing hypotheses, which may vary in terms of their level of detail and sophistication. However, the degree to which theoretical sampling can be deployed depends, in part, on the amount of influence over research design that the research or research team enjoys as well as the timescale involved. Thus, it may be possible to carry out some preliminary analysis before deciding on what basis to augment a sample—that is, carrying out second stage sampling . Some such insights may occur serendipitously or, even, as a result of carrying out parallel quantitative analysis (when, e.g., potentially interesting outliers or intriguing patterning of responses may be identified). Case study research typically involves, from the outset, considerable theorizing as to the important features of different settings or organizations, perhaps at different stages in their gestation or response to a specific set of changes. Here, too, however, fortuitous insights may occur along the way.

Theoretical sampling can also refer to other types of comparative potential recognized and operationalized as the study progresses—for example, some teams have used to comparative advantage the different attributes of team members (e.g., age, gender). Another example might be the realization that a longitudinal approach—or, failing this, an attempt to recruit participants at different stages in their response to a specific phenomenon—might yield important insights.

Theoretical sampling—as does so much in the realm of qualitative research—hinges on finding the most productive balance between structure and spontaneity. The novice researcher has to navigate a course between the somewhat “mystical” (Melia, 1997) accounts involved in some versions of grounded theory, which can emphasize creativity at the expense of rigorous planning and systematic comparison. Although constant comparison forms part of the original formulation of grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), this aspect is often given minimal attention and can be eclipsed by accounts of coding categories and theoretical insights mysteriously “emerging” from the raw data.

In effect, theoretical—or, as it is sometimes called “purposive” sampling provides the key to the comparisons that it will be possible to make during the process of data analysis (Barbour, 2014). Purposive sampling most commonly refers to selecting a sample on the basis of demographic characteristics, such as gender, age, or social class, whereas some references to theoretical sampling relate to the attempt to design a study to explore a specific theoretical framework. In practice, the distinction is frequently blurred, and most theoretical sampling also has comparison at its centre. While some qualitative researchers talk of using sampling strategies in order to explore or test out hypotheses, it is often the case that these are not clearly formulated at the outset of the research, although such ideas are likely to be developed in the course of the study. In marked contrast to quantitative research, where sampling generally needs to be fully articulated prior to any data collection, the iterative nature of the qualitative research endeavour allows for sampling strategies to be refined and augmented as the study progresses. Thus, initial sampling decisions may reflect little more than hunches on the part of researchers; what is crucial, however, is the willingness to subject these to critical scrutiny and to revise where appropriate.

Theoretical sampling—if carried out judiciously and reflectively—can afford the opportunity to apply some structure or strategy, while benefitting from the potential of serendipity and retaining some spontaneity—qualities that are celebrated in much of the qualitative research literature. The next section of this entry explores, in more detail, how a thoughtful and critical approach to sampling can help researchers to make the most of the dual aspects of structure and spontaneity.

Striking a Balance Between Structure and Spontaneity

Even a cursory reading of the huge volume of published qualitative research establishes that those ubiquitous “tools of the trade”—gender and age—feature frequently in descriptions of samples and sampling strategies. However, they are often invoked as a badge of honour rather than being employed as a working concept. It has become common practice in some fields to provide exhaustive details of a sample recruited for a piece of qualitative research, without this information ever being revisited in the course of the ensuing article. Purposive sampling has much more potential than is suggested by this common use as a template for detailing sample demographics; it provides the key to the comparisons that can be made during analysis, drawing on the characteristics that differentiate individuals and subsections of the sample. Often published articles claim to have employed purposive sampling, but, on closer examination, can be seen not to have used this purposefully —to interrogate similarities and differences in perceptions and accounts of research respondents or participants (Barbour, 2014).

Although age and gender—and, importantly, social class—are general sociological standbys and remain at the very centre of much sociological debate and theorizing, these concepts may lose their power when simply imported by researchers versed in other disciplines, who may view these simply as demographic characteristics. Moreover, these may not always be the most relevant criteria to use, as attributes such as religion or locality may have a greater influence on views and experiences, as identified—via the process of analysis—in the patterning that can be observed in the ensuing data. Here the importance of prior knowledge of the field under study is crucial. Perhaps some of the blame for such unfruitful sampling strategies lies with those extreme readings of grounded theory (departing somewhat from the original articulation by Glaser & Strauss, 1967), which veer towards portraying the researcher as entering the field without any preconceptions. Not only is this unrealistic, but it is likely to result in an unreflective and impoverished approach to research design, in general, and sampling strategies, in particular. Indeed, prior knowledge of the specific field under study is crucial to developing effective sampling strategies.

Prior knowledge of the topic or setting under study can yield dividends that are as simple as enabling researchers to identify a research setting that exemplifies the properties in which the researcher is interested—for example, the situation of a specific deprived area, or one with a high percentage of people employed in a particular sector, or one undergoing significant change (e.g., in the wake of a major local government upheaval). This may involve articulating hypotheses, although these can be somewhat tentative at this stage in the research process.

When seeking to find out about patients’ self-management behaviours following a stroke, Emma Boger and colleagues (2015) selected, for their focus groups, patients with a number of characteristics, including clinical features relating to length of time since their stroke and its severity. With regard to the former characteristic, one can see that purposive sampling might, in some circumstances, provide a pragmatic alternative to carrying out longitudinal research. Boger and colleagues (2015), however, do acknowledge that their decision to recruit patients via existing support groups might have meant that they focused on those more likely to be knowledgeable about and motivated towards self-management.

Eva Lena Strandberg and colleagues (2013) provide a further example of researchers drawing on their own professional experience. They sought to compare prescribing behaviours of urban and rural-based family practitioners in southern Sweden. The research was concerned with identifying how context impacted decision-making. Sometimes, of course, such binaries are found not to have the anticipated impact.

Having worked in the field of drug services, Linda Orr (Orr, Barbour, & Elliott, 2013) was already aware of the possible mismatch between the perspectives of carers, front-line service providers, and policymakers. She, therefore, set about eliciting the views and experiences of people in these different roles, with a view to comparing and contrasting their accounts. Alongside the anticipated differences, this sampling approach—and the comparative analysis that followed—also identified some illuminating similarities. One interesting finding was that these three categories were by no means mutually exclusive, as some service providers and policymakers also cared for drug-using family members. Venn diagrams can, therefore, be a useful resource when mapping out sampling strategies and trajectories. Rather than these identified “grey” or overlapping categories giving cause for concern, they may well yield inspiration for developing sampling strategies to allow for targeting, since such individuals—with a “foot in one or more camps”—can function as particularly valuable and insightful commentators.

Focus groups—through their capacity to enlist participants in “problematizing” concepts and discussing differences between their own experiences and those of others—can be particularly fruitful in terms of providing enhanced comparative potential (Barbour, 2007). This method also allows considerable flexibility in terms of sampling strategies, since researchers, in theory, can exert control with regard both to selecting the groups or constituencies they wish to compare and to allocating individuals to groups, since intergroup comparisons can be just as illuminating as can intragroup ones. Convening groups according to different criteria provides the researcher with further comparative—and hence, analytical—potential. Kathleen Powell (2014), for example, was interested in investigating neighbourhood relations in an Appalachian town next to a university campus. She held focus groups with students and year-round residents but elected to also hold some mixed focus groups, allowing her to explore the ways in which members of these two constituencies moderated their views when interacting with representatives of the other group, a situation that, arguably, is closer to real life. Focus groups certainly afford enhanced comparative potential and can afford economies of scale, as is demonstrated by a project carried out by Judith Green and colleagues (2005). This was concerned with public understanding of food risks in Finland, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. While seeking to make international comparisons might appear a daunting task, the researchers rendered this manageable by convening focus groups with people of varying ages and stages in the life cycle. Thus, a relatively small number of focus groups (36 in total) enabled them to tease out those understandings that related to national concerns and values and those which were specifically preoccupied certain subsections of the population.

Riie Heikklä’s (2011) research was explicitly designed to interrogate theoretical understandings—in this case, in relation to the concept of “taste.” To this end, she decided to focus on Swedish-speaking Finns, a choice which also afforded her the opportunity of convening contrasting focus groups, comprising individuals who shared different social class positions. This proved to be a fruitful strategy with Heikklä expressing some surprise at how early, in discussion, it became evident that these groups subscribed to markedly different orientations to taste.

Also placing itself within the wider theoretical context, the research carried out by Paul Thompson and colleagues (2016) set out to reexamine the hypothesis—or widely held assumption, as expressed in the relevant literature—that autonomy is a defining feature of work in the creative industries. This study focused on Australian development studios active in the global digital games industry. The research team also sought to rectify the imbalance between what they call “high theory” and empirical work—of which there has been very little. They articulate their sampling strategy thus:

The selection of (33) interviewees was driven by theoretical considerations rather than statistical sampling; firms were selected to ensure we had access to different market segments (console … mobile … or both … ) and which varied in terms of the age of the firm (1–16 years), number of employees (1–100+) and ownership (domestic … or international … )… … In order to capture fully the labour dynamics in the industry, we conducted a further 20 semi-structured interviews with employees/games developers.” (2016, p. 321)

Thompson and colleagues also—implicitly—invoke the notion of “saturation,” explaining that, once they “achieved a high convergence of responses,” they ceased recruiting for further interviews (2016, p. 321). Saturation is a key component of grounded theory—in relation to both sampling strategies and developing coding categories—although the grounds for making such declarations may be questionable, since it is nearly always possible to spot gaps in sampling and identify new issues and themes if one only looks hard enough at the rich data typically elicited through qualitative methods. However, timetabling and funding constraints generally mean that researchers have to make a judgement call as to when they have recruited enough respondents or generated sufficient data. This will, of course, be dependent on their aims and the coverage they hope to achieve. What the comment from Thompson and colleagues underlines, however, is the extent to which sampling, data elicitation, and preliminary data analysis tend, in practice, to be carried out alongside each other, rather than in the procedural, or staged, manner sometimes suggested by textbook guidance. This particular research project also serves as a vivid reminder of the benefits of employing a structured approach to sampling, even where the aims of the study are couched in overtly theoretical terms. While Thompson and colleagues drew on their prior knowledge of this industry sector to inform their sampling strategy, other researchers have taken a more explicitly structured approach.

Structured Approaches

Although purposive sampling allows for several factors to be taken into account simultaneously, this can present some challenges in practice. Use of a sampling grid (see Table 1 ) can be extremely helpful, both in delineating the potential cells and, particularly, in identifying any gaps in sampling. Since qualitative research generally allows for samples to be augmented and refined as the study progresses, it is possible to take action to attempt to rectify such omissions. When mounting a study of patients’ experiences of weight management in one general practice the researchers wanted to include both men and women, people of varying ages, and, as this practice served an area with a population spanning the relatively affluent and relatively deprived, the researchers hoped to recruit a sample of interviewees that reflected all of these characteristics. Producing a sampling grid ( Table 1 ) allowed the researchers to chart their progress.

As Table 1 shows, it is not always possible to fill all anticipated cells, despite researchers’ best intentions and efforts. Tamsin Hinton-Smith (2016), who carried out a piece of longitudinal research with lone parent students, reflects that, despite repeated targeting, she was able to recruit only two lone fathers. As highlighted earlier, however, applying sampling strategies occurs alongside recruitment processes, and it may sometimes be worth giving consideration to who is attempting to do the recruiting. Guro Kristensen and Malin Ravn (2015) report, for example, that male gatekeepers—or mediators—enjoyed greater success in recruiting expectant fathers. They stress the need to take into account the researcher’s own positioning in the social and cultural landscape—a strand that is frequently overlooked in discussion of sampling strategies.

The work of Vegard Jarness (2017) provides an example of a theoretically driven piece of research, which, nevertheless, employed a structured approach to sampling. This research speaks to contemporary debates on cultural stratification and the symbolic boundary approach to class analysis. The preexisting Oslo Register Data Class Scheme of classification was used in order to identify occupations typical for each category differentiated and Jarness then searched the online yellow pages to find potential interviewees occupying these roles. This provided Jarness with a framework for recruiting participants in different segments within the middle class and allowed him to articulate and explore their mutual symbolic antagonism—that is, the ways in which people actively make distinctions in order to evaluate and classify others either negatively or positively.

Caragh Brosnan (2015) demonstrated the value of a structured approach to identifying relevant media items in order to allow her to critically trace the trajectory of the Friends of Science campaign against the teaching of complementary and alternative medicine in Australian universities. She searched the EBSCO and ProQuest databases, as well as Google, using the same relevant key terms and focused on the period covering the first half of 2012, when the campaign was at its most active.

An electronic database was also used as a sampling frame by Vered Ben-David (2016) who wanted to analyse Israeli court decisions relating to termination of parental rights. Ben-David sampled 130 out of a possible 231 court decisions lodged on the legal database, choosing at least one from each year 1960–2007, further selection being designed to include all cases that had set a legal precedent or that determined ways of interpreting the law or rights of the child, parents, or family unit. She explains that the study “hypothesized that, due to lack of clearly-defined evaluation criteria, judges and professionals engage in social constructions of reality processes related to the child-parent relationship” (2016, p. 518). Since the case reports included detailed demographic information Ben-David’s fine-grained analysis of the transcripts was able to demonstrate how negative views of parenting—as “impaired, failed, dangerous and harmful” (2016, p. 518)—permeate legal discourse and impact on legal decisions.

When embarking on a study with the aim of eliciting the views and experiences of women who had recently given birth with regard to taking folic acid, Rosaline Barbour and colleagues (2012) were reluctant, for ethical reasons, to bring together women who had followed recommended practice and those who had not taken this advice. The researchers, therefore, attempted, by means of a pro forma circulated at baby clinics, to determine which women had taken folic acid during their most recent pregnancy and those who had not. This short questionnaire also collected vital sampling-relevant information, such as parity (number of children), age of mother, deprivation level (deduced from post code of residence—with a score of 1 determining least deprived and 7 most deprived), educational level, and marital status. The information collected from women who had volunteered to take part in focus groups was then used in order to draw up five potential groups, differentiated, firstly, by their behaviour with regard to taking folic acid and, secondly, by parity (with two groups of primiparous women who had only one baby and three groups of multiparous women who had given birth to two or more babies); also seeking to match participants, as far as possible, with regard to age range; deprivation scores; level of education; and marital status. They also had plans in reserve to convene a sixth group, comprising women who had taken folic acid but selected to reflect other characteristics that preliminary analysis suggested might be relevant.

Even this plan proved to be less simple to put into practice than the researchers had anticipated, as further analysis of questionnaire replies revealed that some women had taken folic acid but not exactly as recommended, some had taken folic acid with their most recent pregnancy but not previously, and vice versa. The research team decided to relax their criteria and opted to mix women who had taken folic acid with those who had taken it but not exactly as recommended, although they still sought to separate those who had taken folic acid and those who had not taken it at all. This was a pragmatic decision and this experience shows the complexities behind providing “tick-box” answers and the pitfalls associated with using these as a sampling tool. Fortunately, the researchers had asked for some free text explanation (to allow respondents to expand on their answers), which proved invaluable, leading them to question their initial overly simplistic categorizations. In some contexts, it may also be helpful to use a screening questionnaire to elicit attitudinal responses, which might subsequently be used to select participants known to have similar or contrasting views on key issues.

Opportunities may also be provided by larger projects—particularly where the researcher has been involved in these and has a prior claim on or access to the data generated, whether qualitative or quantitative. Lucy Mayblin and colleagues (2016) took advantage of one such opportunity afforded by a larger project on Poles living in Warsaw. Their privileged access allowed the researchers to select interviewees to cover a range of demographic characteristics—gender, age group, marital status, disability, sexual orientation, nationality, religion, place of birth, and work status. Notably, it is not usually possible to take account of so many criteria when engaging in purposive or theoretical sampling.

Sometimes preliminary fieldwork can be extremely valuable. When commissioned to evaluate service users’ and providers’ responses to termination of pregnancy services in a particular Scottish Health Board area, Áine Kennedy (2005) and Rosaline Barbour (as consultant) realized that they did not have a detailed understanding of the system as currently operated. This led them to produce a flow diagram, which outlined the decision-making points and main “branchings” (characterized by the pathways involved in chemical or surgical options) that determined what service women would receive and which technical or medical procedures staff were required to perform. Kennedy and Barbour then aimed to recruit roughly equivalent numbers of women and service providers involved in all the different aspects identified by their diagram.

Preliminary fieldwork can also help researchers to see whether the distinctions that they have made in their heads actually make sense in the field. Even where this is not possible, it can be extremely helpful to stand back from the question being pursued and to think about how best to achieve maximum diversity in the sample: “Who might you be inadvertently excluding?” Social scientists, as researchers, have long been exhorted to take a somewhat playful approach, following through on the implications of turning their research question on its head; it is this type of exercise that is referred to here. These imaginative approaches also extend to asking the hypothetical question: “What could possibly go wrong?”

Imaginative Approaches

To achieve maximum diversity in their sampling of Latino families, Adriana Umaña-Taylor and Mayra Bámaca (2004) explored options beyond the traditional gatekeepers, and contacted consulates, who were, they reasoned, in an excellent position to advise about the variety of potential focus group participants. Unquestioningly, pursuing tried-and-tested lines of recruitment can lead to sampling by default and may leave important gaps, especially when circumstances have changed since previous studies were carried out. These researchers also found themselves negotiating with children who might act as interpreters and hence, conduits for other family members who did not possess such advanced foreign language skills. Umaña-Taylor and Bámaca were working within the participatory research tradition, where inclusivity was a central concern. Even when this is not the case, researchers can benefit from considering where there may be gaps in their sampling reach. Such attention to detail can yield dividends later in the process, when it comes to considering the limitations of the study—and, ultimately, the transferability of findings.

Participatory studies are sometimes envisaged as lying outside of traditional research design considerations. However, even here, it can be useful to look beyond selection of the obvious stakeholders and key respondents and to take account of the types of knowledge or vantage points from which the study might benefit. Lisa Hardy and colleagues (2016) who actually employed members of the community they were studying, reflect:

In our experience, the most successful candidates for community research positions may have an abundance of local knowledge, community ties, or the ability to inspire participation and engagement from their fellow community members; skills that may not be apparent on a résumé. (p. 595)

Although often conceived of as a separate issue, the choice of research method can also have a marked impact—for good or bad—on the coverage of the resulting sample. The influence of online methods has even extended to ethnographic practice, since, as Gary Alan Fine and Black Hawk Hancock (2017) observe, this approach is no longer (necessarily) grounded in place, but, rather, in social relations—by whichever means these are pursued. The online arena is sometimes hailed as the new panacea, but researchers who opt for this as an easy route to sampling should take time to consider who they may excluding. While Internet access may no longer be the preserve of the financially privileged, Emily Noelle Ignacio (2012) makes the point that diaspora members, for example, are less likely than other groups to be fluent in the language of their host country and may, therefore, be easily overlooked if researchers rely overly on online sampling strategies. There may be other exclusionary practices involved online, which have the unanticipated consequence of restricting contributions—for example, in response to blogs and discussion threads.

Researchers may also fall into the trap of thinking that particular sampling strategies will automatically lead them to the data that they desire. The type of discussion engaged in online may be more limited than researchers anticipate. Magdalena Wojcieszak and Diana Mutz (2009) carried out a comparative exercise and highlight the limits of the scope of discussion generated by political, civic, religious, and ethnic online groupings: These tended to avoid overtly political discussion, with the ethnic group postings, in particular, being characterized by reinforcing (rather than challenging) discussions. In contrast, online professional groups were found to be much more likely to give rise to political discussion.

The caveat from Ignacio (2012) regarding language restrictions was less relevant for Donya Alinejad (2011) who tapped into blogs as a vehicle for accessing the perceptions of second-generation Iranians living in the United States and Canada. She reasoned that these individuals were, however, more likely to suffer from dislocation and were likely to use blogging sites as a vehicle for sharing their experiences with others in a similar situation—making this an ideal data source and thereby doing much of the work of sampling. However, when researchers rely on “harvesting” online material not originally generated for research purposes, they lose control with regard to collecting additional demographic information about participants, which can limit the potential for systematic comparison.

When researchers are seeking to recruit those deemed “hard to reach,” the online format may have particular advantages. David Nicholas and colleagues (2010) enjoyed considerable success in engaging through this medium with children with cerebral palsy, spina bifida, or cystic fibrosis, recording favourable comments that suggested that other approaches may not have been as fruitful. Even when hard-to-reach populations are not the immediate focus of the research, it may be worth considering the inclusion of an online option, in order to potentially expand sample diversity through making the research more accessible and attractive to those who might otherwise be reluctant to take part. Richard Wood and Mark Griffiths (2007), for example, commented that their online research with gamblers allowed them to access individuals who could be described as being “socially unskilled.”

Discussing elite interviews (Harvey, 2011) emphasizes that those individuals occupying the most important social network, social capital, and strategic positions are not necessarily the most obvious, or apparently senior, people. It pays, therefore, to cast one’s sampling net more widely. For example, Robert Mikecz (2012) also involved in interviewing elites—in his case the Estonian economic elite—sought also to recruit former government ministers. Recent retirees may be a valuable and largely untapped resource and may even be more forthcoming than those still in post, since they may feel they have less to lose by making research-relevant disclosures. Mikecz also highlighted the usefulness of engaging in background reading, including texts written by and about the individuals he was studying. He adds the observation that being able to demonstrate his interest and knowledge in this way frequently gave rise to opportunities for snowball sampling (augmenting the sample through using respondents’ networks).

Particularly when attempting to gain access to subcultural worlds, researchers need to think creatively, as ready-made sampling frames are unlikely to exist. Jon Garland and colleagues (2015) detail their efforts involving spending time in the field so as to develop contacts in order to access potential interviewees. This project generated life story data through interviews about victimization and violence against people belonging to alternative subcultures. The researchers report that they carried out participant observation at a music festival that attracted a largely nu metal, goth and punk audience and explain that they also relied on word-of-mouth and snowball sampling in order to recruit volunteers. Prior engagement and establishment of trust was crucial since “Potential interviewees had to define themselves as coming from an alternative subculture and, in line with the project’s key aims, must have previously been victimized because of that identity characteristic” (p. 1068). While relying on interviewees to volunteer, the sampling requirements were fairly stringent and these could have only been applied via a process of immersion in the field.

It is not, however, always necessary to carry out fresh sampling, as comparative potential can be achieved through drawing together separate studies and capitalizing on their varied coverage. Fiona Smith and colleagues (2010) reanalysed data generated via a range of qualitative methods throughout three previous projects on volunteering. As all had a biographical focus, they were able to explore the social and relational nature of volunteering in differing localities. This provides an interesting example of retrospective sampling in relation to ethnographic studies, allowing the authors to carry out comparative analysis in order to address disciplinary concerns within the field of social geography.

Although ethnographies tend to be setting-specific, it is still worth considering ways of building in a comparative element. If the trend towards compressed timetables and resulting condensed fieldwork continues, it will be even more important to give due consideration to the selection of sites for such short ethnographic encounters (Fine & Hancock, 2017). Even when only one fieldwork site is covered, it may be possible to enhance comparative potential by choosing particular events or time slots for observational fieldwork. Some events may be restricted to either men or women, or participants of different ages, and, in such cases, the make-up of the research team can be helpful in allowing access to different events, which may shed a useful comparative focus on the organization or society under study.

Sharyn Roach Anleu and colleagues (2016) describe their approach to carrying out observational fieldwork, exploring how emotions were managed and how these influenced interactions and processes involved in judicial work in the Swedish context. In this study, the two researchers worked in different parts of the country, with each focusing on two courts in these separate areas including the shadowing, at different times, of prosecutors and judges, with the researchers observing them in court and in their offices. A novel aspect of this study, however, was the decision to exchange sites, affording the opportunity for the researchers to compare notes and, thus, personalize and make explicit the comparative work involved in analysis. As such strategies are likely to be costly, however, both in terms of time and in terms of money, researchers may have to consider other ways of enhancing comparative potential.

When carrying out the observational component of a mixed-methods study looking at the role and responsibilities of midwives in Scotland, Janet Askham and Rosaline Barbour (1996) were interested in how midwives and members of the medical staff negotiated decision-making and, in particular, how they managed any disagreement. They concluded that it would be important to include observation of night duty, as this significantly altered the context of work and deployment of different members of staff, with midwives frequently having to decide when to contact doctors, whereas, during the day shift, members of the medical staff were more likely to already be on hand.

With regard to this study, several settings were chosen in order to afford opportunity for comparison. These were selected to cover a number of different geographical/Health Board areas and included large teaching hospitals (with a full component of consultants, senior registrars, registrars, and medical students, as well as different grades of midwives and student midwives); smaller general practitioner-led units, where doctors visited intermittently and midwives ran the unit on a day-to-day basis; and community settings (where midwives carried out the bulk of their work outside of the confined of the hospital and the gaze of medical staff). Analysis confirmed that the type and content of negotiation was very different in these various settings, with responsibilities being allocated according to pragmatic criteria as well as being dependent upon relationships between doctors and midwives that might have been built up over many years of working together.

Although the authors did not label this project as case study research, their decision-making was very much in line with the rationale that might be invoked with regard to selection of settings for this type of qualitative research. Whether selection involves one or more cases, it is generally based on initial theorizing as to what sort of lens or insights the setting will afford with regard to illuminating the particular phenomenon under study.

Selecting Sites or Case Studies

Although the term theoretical sampling is not commonly used in relation to case study research, much of the debate and guidance that has been produced does, in effect, rely on making effective sampling decisions.

Adriana Espinoza and colleagues (2014) sought to study responses of residents in Chile to the country’s turbulent past through focusing on what they termed “sites of memory”—defined as “those urban spaces that while making reference to the past are also used by people as scenery to talk about the past, constructing and deconstructing interpretations about their own history and the country’s past” (p. 716). The choice of sites was informed by the researchers’ insider knowledge as fellow citizens as to which settings had the “most symbolic relevance in terms of remembering the violation of human rights during [Augusto Pinochet’s] dictatorship” (p. 717).

Since the research concerned events within living memory, Espinoza and colleagues also chose to compare the perceptions of three distinct cohorts, with different experience of these events: those aged 60 years and over (who had been young adults at the time of the 1973 coup d’état), 30- to 60-year-olds (who had lived through it), and 18- to 30-year-olds (born after the end of Pinochet’s dictatorship). Unlike the somewhat arbitrary appeals to age differences that some researchers advance to justify their sampling decisions, Espinoza and colleagues’ rationale (involving an innovative mixture of walking and talking in order to generate data) was theoretically informed, recognizing the “complexity of studying collective memory processes and generational discourse at memory sites in [a country] with [a] traumatic past” (p. 712). They explain: “meanings about the past are dynamic, unstable, and depend both on the social positions from which they are enunciated and on the contexts in which they circulate and are discussed” (p. 719).

John Gerring (2008) outlines the different rationales for selecting “cases” for research purposes, implicitly invoking the notion of theorizing and the potential for comparison—particularly if different types of cases are selected:

- Typical —selection of one site that is deemed likely to reflect the situation elsewhere.

- Diverse —selection of sites in order to afford the greatest range or variation with regard to a specific feature that is of interest. (See, e.g., the midwives study discussed earlier, where the researchers sought to include all types of maternity unit—and staffing set-up—in existence at the time.)

- Extreme —selected because it is located at one or other end of the possible spectrum. The delineation of the spectrum and what it covers will depend on the topic being researched.

- Deviant —selecting an exception or outlier, with the intention of using this to highlight general principles (in line with the approach referred to as Critical Incident Technique—as first developed in the aeronautical industry in order to learn from “near misses” or accidents).

- Influential— selection on this basis is most likely to occur within the context of studies seeking to explore discipline-specific issues; for example, perhaps involving a frequently cited organizational setting, which has given rise to attempts at replication.

- Crucial— selection of a setting that is judged most likely to demonstrate a particular outcome. This rationale for selection relates most frequently to situations in which researchers wish to test, develop, or elaborate a specific theoretical model.

- Pathway— selection of a setting that embodies a distinct causal pathway, suggesting both prior knowledge of the field and a commitment to a modelling approach. (Adapted from Gerring, 2008)

This breakdown from Gerring provides a useful menu, which can be perused in deciding which elements to select. This will, of course, depend on the sort of comparison one wishes to make: The most commonly used template tends to be a combination of diverse and extreme cases. Gerring also discusses the potential of broader approaches, such as selecting “most similar cases” (chosen to be similar in all respects, except for one crucial difference) or “most different cases” (whereby researchers seek to reflect maximum variation).

It is relatively rare to find detailed accounts of the development of sampling strategies with regard to ethnographic work. An exception is provided by Elisabeth Jean Wood (2006) who carried out fieldwork in El Salvador, while the civil war was still unfolding. Practicalities and safety were uppermost amongst her considerations, but she looked for sites that differed in terms of social relations prior to the war (whether areas had been characterized by wage labour, sharecropping, or peasant agriculture) and patterns of political mobilization—to include both areas supporting political insurgents and those supporting the government. Although, in terms of research design considerations, Wood comments that she would, ideally, have liked to have included areas with no insurgent activity (an “extreme” case in Gerring’s typology), but that such areas were more dangerous places for a researcher to be.

Focusing on the everyday practices involved in the flagging of nationhood, an observational study illuminated the ways in which public and commercial enterprises invoked and utilized national markers (e.g., flags and other symbols; Skey, 2017). Having selected study sites in both England and Wales and seeking to include urban and rural settings, Michael Skey explains that areas were chosen to contain the widest range of shops and public and other institutions and were, hence, deemed likely to have the richest visual signscapes. This research also sought to address—through paying attention to the demographics, government type, corporate and organizational involvement/investment, and history of geographical areas—issues relating to devolution, colonization, and European integration. Thus, potential for comparison between sites was ensured, and this aim was central to the design of the study. Paying attention to the wider context in which the research was being carried out, further consideration was given to the timing of observational fieldwork, in order to avoid major events, which might have prompted increased use of nationhood signifiers.

Specific events, whether anticipated or not, may be extremely valuable in throwing issues into sharp focus. Whether these should be avoided or embraced depends, ultimately, on the aims of the research in question. Elizabeth Black and Philip Smith (1999), for example, seized the opportunity afforded by the untimely death of Princess Diana to mount a focus group study that explored Australian women’s responses to a range of related public discourses and representations.

Serendipity can yield further insights—provided that the researcher remains alert to this potential and that she or he is prepared to adjust her or his sampling categories accordingly.

Capitalizing on Serendipity

The topic of Max Morris and Eric Anderson’s (2015) research was “inclusive masculinity,” as currently articulated and received online. This related to expressions of a softer, gay-friendly, and feminist-oriented “new masculinity.” They focused on posts from the United Kingdom’s four most popular male vloggers, as determined by their number of subscribers—mainly drawn from the generation sometimes referred to as “millennials” born after 1990. Their sampling was facilitated by YouTube’s search options, which allowed them to select by date and popularity of posts. Although they concentrated on posts uploaded between September 2012 and September 2013, Morris and Anderson noted that three out of the four vloggers selected had been creating videos for longer than the period covered by the study. They opted, therefore, to include these individuals’ 20 most-watched videos, noting that these were, occasionally, collaborative ventures.

As Barbour and colleagues (2012) discovered in the course of sampling for focus groups in their folic acid study, having one’s preconceptions challenged can be very instructive; as such complications—indeed, mistakes—can, in effect, provide one with data. Karen Cuthbert (2017) set out to look at the experiences of those who were both disabled and asexual (defined as someone who does not experience sexual attraction). She reflects on the surprises in store as she came to recognize the extent to which her respondents were actually multidimensional.

during the research I came to realise … the multi-layered and intersectional nature of identities … I had naively assumed asexuality and disability would be the most salient aspects of participants’ identities … but this was rarely the case. Therefore, with each participant there were points of difference as well as commonality. (p. 245)

This led Cuthbert to explore the ways in which gender and social class further mediated the experiences of her respondents. This illustrates the often-overlooked potential of retrospective sampling —that is, using the characteristics uncovered in the sample to advantage in making comparisons during the process of analysis. Even when studies have relied on convenience samples, it is possible to benefit from such a retrospective purposive glance.

The original advice on operationalizing grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) allowed for researchers returning to the field, in order to further test their emergent hypotheses. Timetabling and funding constraints mean that this is seldom carried out; nevertheless, this is where theoretical sampling can come into its own. However, this was an opportunity that presented itself in a study looking at the views and experiences of general practitioners (GPs) in relation to issuing sickness certificated to patients (Hussey et al., 2004). The researchers had initially held seven focus groups in a number of geographical areas, seeking to achieve a spread in terms of single-handed, medium-sized, and large group practices, and in terms of the length of experience of GPs. In the course of the preliminary analysis of these seven focus group transcripts, the research team was alerted to the possibility that contrasting employment situations led GPs to view the issues involved in somewhat different ways. They, therefore, elected to convene three further focus groups with GPs belonging to the three categories of locums (who worked across a range of practices, as required), registrars (who were still undergoing advanced training), and GP principals (practice leads with management responsibilities). Comparing the data generated in these further three groups afforded the researchers’ insights into how concerns about career progression, job security, and ongoing relationships with patients and with colleagues operated to mediate perceptions and, indeed, behaviour, in relation to issuing sickness certificates. That this required only three further focus groups (held with individuals from the original sampling pool and who could have been assigned to the original groups) testifies to the enhanced comparative potential that focus groups can afford—provided that researchers remain alert to the possibilities of second-stage sampling (Barbour, 2007). Incidentally, the researchers were alerted to these important comparative insights because they had paid attention to individual voices while data were being generated (through meticulous note-taking) and during the process of preliminary analysis.

Research carried out by Jarness (2017; discussed earlier in relation to its use of a national classification scheme) also enabled further second-level sampling to be carried out, as the classification scheme allowed for an unusually detailed distinction to be made in sampling for subtle differences in social class position. This also provides an example of how apparently realist criteria can be usefully pressed into service in addressing constructivist or theoretical concerns. The study was designed to address contemporary sociological debates regarding cultural stratification, providing an insight into a symbolic boundary approach to class analysis. It sought to explore differences between members of the same social class, looking at the ways in which they evaluated and classified others and illuminated the ways in which intraclass divisions and mutual symbolic antagonism were expressed and enacted.

Virtually, every qualitative research project can be strengthened by encompassing some variant of theoretical sampling. While qualitative research is frequently lauded for its capacity to provide in-depth and contextualized understandings of complex phenomena, behind such nuanced and theorized accounts lies considerable effort in terms of paying attention to sampling issues. Although researchers may not always labour the details of how they developed and implemented sampling strategies, these, nevertheless, lie at the root of good-quality qualitative studies and are, ultimately, the deciding features that differentiate between purely descriptive and analytically advanced accounts. It does, however, need to be acknowledged that a degree of “sleight-of-hand” can be involved in the production of published accounts of qualitative research, with explanations of purposive and theoretical sampling being inserted retrospectively for the sake of appearance rather than having driven the research from the outset. Ultimately, however, this may perhaps not matter too much, if the object of the exercise is to learn and reflect on how researchers can press theoretical sampling into service with regard to strengthening their own future research endeavours.

Theoretical sampling is the key to ensuring both that the data generated speak to a range of voices and experiences and that the ensuing findings are cognizant of similarities and differences. Qualitative research—particularly ethnographic work with an overtly constructivist orientation—is sometimes criticized for its micro focus, and, hence, the assumed inability of findings to transcend the contingent and specific context in which data are generated. A considered approach to theoretical or purposive sampling affords an opportunity to address realist concerns regarding transferability or the limitations that can or should be placed around findings that illuminate the process of social construction. Theoretical sampling is, thus, the cornerstone of theoretical generalizability, supplying the mechanism through which qualitative researchers can answer the question posed by Uwe Flick (2007): “Do your analytic categories suggest any generic processes?” (p. 11).

Alinejad , D. ( 2011 ). Mapping homelands through virtual spaces: Transnational embodiment and Iranian diaspora bloggers . Global Networks , 11 , 43 – 62 . doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0374.2010.00306.x

Anleu , S. R. , Blix , S. B. , Mack , K. , & Wettergren , A. ( 2016 ). Observing judicial work and emotions: Using two researchers . Qualitative Research , 16 , 375 – 391 . doi: 10.1177/1468794115579475

Askham , J. , & Barbour , R. S. ( 1996 ). The negotiated role of the midwife in Scotland . In S. Robinson & A. M. Thomson (Eds.), Midwives, research and childbirth (Vol. 4 , pp. 33 – 59 ). London, England : Chapman and Hall .

Barbour , R. ( 2007 ). Doing focus groups . London, England : SAGE .

Barbour , R. ( 2014 ). Introducing qualitative research: A student’s guide ( 2nd ed. ). London, England : SAGE .

Barbour , R. S. , MacLeod , M. , Mires , G. , & Anderson , A. S. ( 2012 ). Uptake of folic acid supplements before and during pregnancy: Focus group analysis of women’s views and experiences . Journal of Human Nutrition and dietetics , 25 , 140 – 147 . doi: 10.1111/j.1365-277X.2011.01216.x

Ben-David , V. ( 2016 ). Are they guilty of their parental behaviour? Parenting forms constructed on termination of parental rights court cases . Qualitative Social Work , 15 , 518 – 532 . doi: 10.1177/1473325015595459

Black , E. , & Smith , P. ( 1999 ). Princess Diana’s meanings for women: Results of a focus group study . Journal of Sociology , 35 , 263 – 278 . doi: 10.1177/144078339903500301

Boger , E. J. , Demain , S. H. , & Later , S. M. ( 2015 ) Stroke self-management: A focus group study to identify the factors influencing self-management following stroke . International Journal of Nursing Studies , 52 , 175 – 187 . doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.05.006

Brosnan , C. ( 2015 ). Quackery in the academy? Professional knowledge, autonomy and the debate over complementary medicine degrees . Sociology , 49 , 1047 – 1064 . doi: 10.1177/0038038514557912

Cuthbert , K. ( 2017 ). You have to be normal to be abnormal: An empirically grounded exploration of the intersection of asexuality and disability . Sociology , 51 , 241 – 257 . doi: 10.1177/0038038515587639

Espinoza , A. E. , Piper , I. , & Fernández , R. A. ( 2014 ). The study of memory sites through a dialogical accompaniment interactive group method: A research note . Qualitative Research , 14 , 712 – 728 . doi: 10.1177/1468794113483301

Fine , G. A. , & Hancock , B. H. ( 2017 ). The new ethnographer at work . Qualitative Research , 17 , 260 – 268 .

Flick , U. ( 2007 ). Managing quality in qualitative research . London, England : SAGE .

Garland , J. , Chakraborti , N. , & Hardy , S.-J. ( 2015 ). It felt like a little war: Reflections on violence against alternative subcultures . Sociology , 49 , 1065 – 1080 . doi: 10.1177/0038038515578992

Gerring , J. ( 2008 ). Case selection for case study analysis: Qualitative and quantitative techniques . In J. M. Box-Steffensmeier , H. E. Brady , & P. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp. 645 – 684 ). Oxford, England : Oxford University Press .

Green , J. M. , Draper , A. K. , Dowler , E. A. , Fele , G. , Hagenhoff , V. , Rusanen , M. , & Rusanen , T. ( 2005 ). Public understanding of food risks in four European countries: A qualitative study . European Journal of Public Health , 15 , 523 – 527 . doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cki016

Hardy , L. J. , Hughes , A. , Hulen , E. , Figueroa , A. , Evans , C. , & Begay , R. C. ( 2016 ). Hiring the experts: Best practices for community-engaged research . Qualitative Research , 16 , 592 – 600 . doi: 10.1177/1468794115579474

Harvey , W. S. ( 2011 ). Strategies for conducting elite interviews . Qualitative Research , 11 , 431 – 441 . doi: 10.1177/1468794111404329

Heikklä , R. ( 2011 ). Matters of taste? Conceptions of good and bad taste in focus groups with Swedish-speaking Finns . European Journal of Cultural Studies , 14 , 41 – 61 .

Hinton-Smith , T. ( 2016 ). Negotiating the risk of debt-financed higher education: The experience of lone parent students . British Educational Research Journal , 42 , 207 – 222 . doi: 10.1002/berj.3201

Hussey , S. , Hoddinott , P. , Dowell , J. , Wilson , P. , & Barbour , R. S. ( 2004 ). The sickness certification system in the UK: A qualitative study of the views of general practitioners in Scotland . British Medical Journal , 328 , 88 – 92 . doi: 10.1136/bmj.37949.656389.EE

Ignacio , E. N. ( 2012 ). Online methods and analyzing knowledge-production: A cautionary tale . Qualitative Inquiry , 18 , 237 – 246 .

Jarness , V. ( 2017 ). Cultural vs. economic capital: Symbolic boundaries within the middle class . Sociology , 51 , 357 – 373 . doi: 10.1177/0038038515596909

Kennedy , Á. ( 2005 ). Living with a secret: An action research report on women and service providers views of the termination of pregnancy services . Glasgow, Scotland : Family Planning Association Scotland .

Kristensen , G. K. , & Ravn , M. N. ( 2015 ). The voices heard and the vices silenced: Recruitment processes in qualitative interview studies . Qualitative Research , 15 , 722 – 737 . doi: 10.1177/1468794114567496

Mayblin , L. , Piekut , A. , & Valentine , G. ( 2016 ). Other posts in other places: Poland through a postcolonial lens . Sociology , 50 , 60 – 76 . doi: 10.1177/0038038514556796

Melia , K. M. ( 1997 ). Producing plausible stories: Interviewing student nurses . In G. Miller & R. Dingwall (Eds.), Context and method in qualitative research (pp. 26 – 36 ). London, England : SAGE .

Mikecz , R. ( 2012 ). Interviewing elites: Addressing methodological issues . Qualitative Inquiry , 18 , 482 – 493 . doi: 10.1177/1077800412442818

Morris , M. , & Anderson , E. ( 2015 ). Charlie is so cool like: Authenticity, popularity and inclusive masculinity on YouTube . Sociology , 49 , 1200 – 1217 . doi: 10.1177/0038038514562852

Nicholas , D. B. , Lach , L , King , G. , Scott , M. , Boyell , K. , Sawatzky , B. J. , … Young , N. L. ( 2010 ) Contrasting Internet and face-to-face focus groups for children with chronic health conditions: Outcomes and participant experiences . International Journal of Qualitative Methods , 9 , 105 – 121 . doi: 10.1177/160940691000900102

Orr , L. , Barbour , R. S. , & Elliott , L. ( 2013 ). Carer involvement in drug services: A qualitative study . Health Expectations , 16 , 60 – 72 . doi: 10.1111/hex.12033

Powell , K. H. ( 2014 ). In the shadow of the ivory tower: An ethnographic study of neighborhood relations . Qualitative Social Work , 13 , 108 – 126 . doi: 10.1177/1473325013509299

Skey , M. ( 2017 ). Mindless markers of the nation: The routine flagging of nationhood across the visual environment . Sociology , 51 , 274 – 289 . doi: 10.1177/0038038515590754

Smith , F. M. , Timbrell , H. , Woolvin , M. , Muirhead , S. , & Fyfe , N. ( 2010 ). Enlivened geographies of volunteering: Situated, embodied and emotional practices of voluntary action . Scottish Geographical Journal , 126 , 258 – 274 . doi: 10.1080/14702541.2010.549342

Strandberg , E. L. , Brorsson , A. , Hagsta , C. , Troein , M. , & Hedin , K. ( 2013 ). I’m Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde: Are GPs’ antibiotic prescribing patterns contextually dependent? A qualitative focus group study . Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care , 31 , 158 – 165 . doi: 10.3109/02813432.2013.824156

Thompson , P. , Parker , R. , & Cox , S. ( 2016 ). Interrogating creative theory and creative work: Inside the games studio . Sociology , 50 , 316 – 332 . doi: 10.1177/0038038514565836

Umaña-Taylor , A. J. , & Bámaca , M. Y. ( 2004 ). Conducting focus groups with Latino populations: Lessons from the field . Family Relations , 53 , 261 – 272 . doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.0002.x

Wojcieszak , M. E. , & Mutz , D. C. ( 2009 ). Online groups and political discourse: Do online discussion spaces facilitate exposure to political disagreement? Journal of Communication , 59 , 40 – 56 . doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.01403.x

Wood , E. ( 2006 ). The ethical challenges of field research in conflict zones . Qualitative Sociology , 29 , 373 – 386 . doi: 10.1007/s11133-006-9027-8

Wood , R. T. A. , & Griffiths , M. D. ( 2007 ). Online data collection from gamblers: Methodological issues . International Journal of Mental Health Addiction , 5 , 151 – 163 .

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Please sign into your institution before accessing your profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

Adapting and blending grounded theory with case study: a practical guide

- Published: 08 December 2023

- Volume 58 , pages 2979–3000, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Charles Dahwa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7705-4627 1

971 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

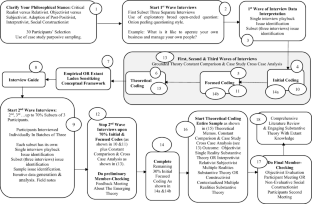

This article tackles how to adapt grounded theory by blending it with case study techniques. Grounded theory is commended for enabling qualitative researchers to avoid priori assumptions and intensely explore social phenomena leading to enhanced theorization and deepened contextualized understanding. However, it is criticized for generating enormous data that is difficult to manage, contentious treatment of literature review and category saturation. Further, while the proliferation of several versions of grounded theory brings new insights and some clarity, inevitably some bits of confusion also creep in, given the dearth of standard protocols applying across such versions. Consequently, the combined effect of all these challenges is that grounded theory is predominantly perceived as very daunting, costly and time consuming. This perception is discouraging many qualitative researchers from using grounded theory; yet using it immensely benefits qualitative research. To gradually impart grounded theory skills and to encourage its usage a key solution is to avoid a full-scale grounded theory but instead use its adapted version, which exploits case study techniques. How to do this is the research question for this article. Through a reflective account of my PhD research methodology the article generates new insights by providing an original and novel empirical account about how to adapt grounded theory blending it with case study techniques. Secondly, the article offers a Versatile Interview Cases Research Framework (VICaRF) that equips qualitative researchers with clear research questions and steps they can take to effectively adapt grounded theory by blending it with case study techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Grounded Theory Methodology: Principles and Practices

Allwood, C.M.: The distinction between qualitative and quantitative research methods is problematic. Qual. Quant. 46 (5), 1417–1429 (2012)

Article Google Scholar

Andrade, A.D.: Interpretive research aiming at theory building: adopting and adapting the case study design. Qual. Rep. 14 (1), 42–60 (2009)

Google Scholar

Bruscaglioni, L.: Theorizing in grounded theory and creative abduction. Qual. Quant. 50 (5), 2009–2024 (2016)

Burrell, G., Morgan, G.: Sociological Paradigms and Organizational Analysis: Elements of the Sociology of Corporate Life. Heinemann, London (1979)

Chalmers, A.F.: What is This Thing Called Science? Open University Press, Maidenhead (1999)

Chamberlain, G.P.: Researching strategy formation process: an abductive methodology. Qual. Quant. 40 , 289–301 (2006)

Charmaz, K.: Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Research. Sage Publications Ltd, London (2006)

Charmaz, K.: Constructing Grounded Theory. SAGE, London (2014)

Cooke, F.L.: Concepts, contexts, and mindsets: putting human resource management research in perspectives. Hum. Resour. Manag. 28 (1), 1–13 (2017)

Cope, J.: Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrep. Theory Pract. 29 (4), 373–397 (2005)

Corbin, J., Strauss, A.: Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 4th edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (2015)

Creswell, J.W.: Qualitative Inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches, 3rd edn. Sage Publications Ltd., London (2013)

Dey, I.: Grounding Grounded Theory: Guidelines for Qualitative Inquiry. Academic, San Diego, CA (1999)

Diefenbach, T.: Are case studies more than sophisticated storytelling?: Methodological problems of qualitative empirical research mainly based on semi-structured interviews. Qual. Quant. 43 (6), 875–894 (2009)

Dunne, C.: The place of the literature review in grounded theory research. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 14 (2), 111–124 (2011)

Fairhurst, G.T., Putnam, L.L.: An integrative methodology for organizational oppositions: aligning grounded theory and discourse analysis. Organ. Res. Methods 22 (4), 917–940 (2019)

Francis, J.J., Johnston, M., Robertson, C., Glidewell, L., Entwistle, V., Eccles, M.P., Grimshaw, J.M.: What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol. Health 25 (10), 1229–1245 (2010)

Glaser, B.: Doing Grounded Theory: Issues and Discussions. Sociology Press, Mill Valley, CA (1998)

Glaser, B.G., Strauss, A.L.: The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter, Chicago, IL (1967)

Gordon, J.: The voice of the social worker: a narrative literature review. Br. J. Soc. Work. 48 (5), 1333–1350 (2018)

Hlady-Rispal, M., Jouison-Laffitte, E.: Qualitative research methods and epistemological frameworks: a review of publication trends in entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 52 (4), 594–614 (2014)

Iman, M.T., Boostani, D.: A qualitative investigation of the intersection of leisure and identity among high school students: application of grounded theory. Qual. Quant. 46 (2), 483–499 (2012)

Katz, J.A., Aldrich, H.E., Welbourne, T.M., Williams, P.M.: Guest editor’s comments special issue on human resource management and the SME: toward a new synthesis. Entrep. Theory Pract. 25 (1), 7–10 (2000)

Kibuku, R.N., Ochieng, D.O., Wausi, A.N.: Developing an e-learning theory for interaction and collaboration using grounded theory: a methodological approach. Qual. Rep. 26 (9), 0_1-2854 (2021)

Lai, Y., Saridakis, G., Johnstone, S.: Human resource practices, employee attitudes and small firm performance. Int. Small Bus. J. 35 (4), 470–494 (2017)

Lauckner, H., Paterson, M., Krupa, T.: Using constructivist case study methodology to understand community development processes: proposed methodological questions to guide the research process. Qual. Rep. 17 (13), 1–22 (2012)

Levers, M.J.D.: Philosophical paradigms, grounded theory, and perspectives on emergence, pp. 1–6. Sage Open, London (2013)

Marlow, S.: Human resource management in smaller firms: a contradiction in terms? Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 16 (4), 467–477 (2006)

Marlow, S., Taylor, S., Thompson, A.: Informality and formality in medium sized companies: contestation and synchronization. Br. J. Manag. 21 (4), 954–966 (2010)

Mason, M.: Sample size and saturation in PhD studies using qualitative interviews. Qual. Soc. Res. (2010). https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-11.3.1428

Mauceri, S.: Mixed strategies for improving data quality: the contribution of qualitative procedures to survey research. Qual. Quant. 48 , 2773–2790 (2014)

Mullen, M., Budeva, D.G., Doney, P.M.: Research methods in the leading small business entrepreneurship journals: a critical review with recommendations for future research. J. Small Bus. Manage. 47 (3), 287–307 (2009)

Niaz, M.: Can findings of qualitative research in education be generalized? Qual. Quant. 41 (3), 429–445 (2007)

Nolan, C.T., Garavan, T.N.: Human resource development in SMEs: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 18 (1), 85–107 (2016)

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., Leech, N.L.: A call for qualitative power analyses. Qual. Quant. 41 (1), 105–121 (2007)

Pentland, B.T.: Building process theory with narrative: from description to explanation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 24 (4), 711–724 (1999)

Popper, K.: The Logic of Scientific Discovery. Hutchinson, Tuebingen (1959)

Ramalho, R., Adams, P., Huggard, P., Hoare, K.: Literature review and constructivist grounded theory methodology. Qual. Soc. Res. J. 16 (3), 1–13 (2015)

Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., Jinks, C.: Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual. Quant. 52 , 1893–1907 (2018)

Sharma, G., Kulshreshtha, K., Bajpai, N.: Getting over the issue of theoretical stagnation: an exploration and metamorphosis of grounded theory approach. Qual. Quant. 56 (2), 857–884 (2022)

Stake, R.E.: The Art of Case Study Research. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA (1995)

Strauss, A.L., Corbin, J.: The Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Sage, Newbury Park, CA (1998)

Thistoll, T., Hooper, V., Pauleen, D.J.: Acquiring and developing theoretical sensitivity through undertaking a grounded preliminary literature review. Qual. Quant. 50 (2), 619–636 (2016)

Tobi, H., Kampen, J.K.: Research design: the methodology for interdisciplinary research framework. Qual. Quant. 52 , 1209–1225 (2018)